This article originally appeared at Your Local Epidemiologist New York. Sign up for the YLE NY newsletter here. Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

We’re seeing movement on multiple infectious disease fronts in New York this week. The Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in Harlem has more than doubled. Rabies is elevated in some counties. And across the state, West Nile virus is rising with mosquito activity. This week’s post will cover what these mean for your health, and how to reduce your risk. Let’s dive in.

Legionnaires’ outbreak grows

The cluster of Legionnaires’ disease in Harlem we reported on last week continues to grow. As of Thursday, there were 73 cases, including three deaths. Affected ZIP codes are: 10027, 10030, 10035, 10037, and 10039. The risk to most is low, but if you live or work around these ZIP codes and have flu-like symptoms, it’s important to see a health care provider immediately for possible antibiotic treatment. If you do not have a health care provider, visit NYC Health + Hospitals.

Legionnaires’ disease symptoms include:

- Cough

- Fever

- Chills

- Muscle aches

- Shortness of breath

Most people exposed to Legionella bacteria won’t show symptoms, but the bacteria is particularly risky for people who are over 50, people who smoke or who have chronic lung disease, and those with weakened immune systems. The most recent New York City Legionnaires’ report showed that among people infected in 2019-22, more than 90% had at least one chronic medical condition, and more than 50% were previous or current smokers. The most commonly cited medical conditions were diabetes and lung disease.

For outbreaks like this in New York City, the culprit is most likely a cooling tower. These usually sit on roofs and use water evaporation to cool the building. When bacteria-containing mist from a contaminated cooling tower drifts down, people can breathe it in and get infected. This means that residents in these ZIP codes can continue to drink tap water, bathe, shower, cook, and use their air conditioners.

That’s because cooling towers and drinking water tanks are different systems — it’s not the same water.

We’ve had several Legionella outbreaks here linked to cooling towers previously. Every year, there are hundreds of cases detected in New York City.

During the pandemic, cases actually declined compared to the previous couple of years. Masking and less movement around the city probably reduced exposure to mist from cooling towers, where Legionella can grow.

In 2015, one of the biggest outbreaks of Legionnaire’s disease in the United States was linked to a single cooling tower in the Bronx. That tower was responsible for 135 cases and 16 deaths.

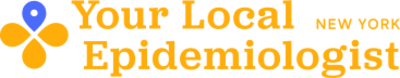

In New York City, Legionnaires’ disease tends to be more common in Northern Manhattan and the Bronx. The reasons aren’t totally understood, but it’s likely due to a mix of factors, including lower maintenance of building systems like cooling towers (often tied to income and infrastructure disparities) and higher rates of chronic health conditions like diabetes, which can increase risk of severe infection.

So, how can we prevent outbreaks?

In New York, the best way to prevent outbreaks is to test and treat cooling towers. Legionella bacteria is actually quite common in the environment, and a positive test doesn’t always mean there will be an outbreak. Still, New York has a system. Under state law, all cooling towers must be:

- Registered with the state

- Tested for bacteria

- Cleaned and disinfected after testing

- Maintained under a long-term management plan

These requirements apply to all cleaning towers, including residential buildings, schools, office buildings, and businesses. When Legionella is detected, the tower must be cleaned and retested until it meets safety standards.

What does this mean for me?

While Legionella is common in the environment, most people exposed won’t get sick. But when conditions are right, and there are vulnerable groups living or working close to sources, exposure can lead to serious illness. If you live or work in one of the affected ZIP codes and have or develop flu symptoms, seek medical care as soon as possible. Early detection, proper maintenance, and rapid public health investigation are key.

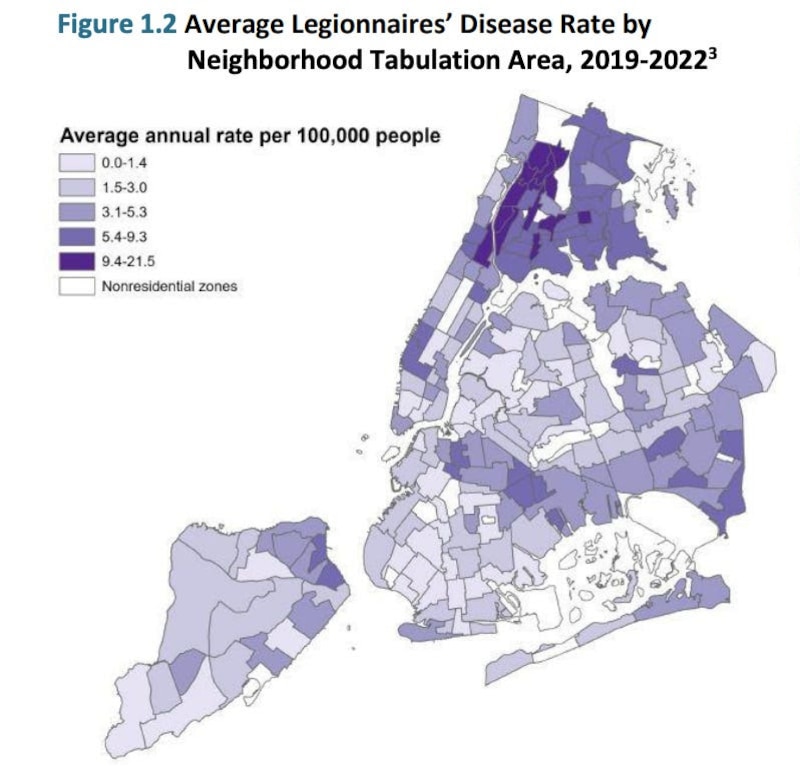

Rabies in Nassau

Rabies is increasing in some New York communities. Nassau County just declared rabies an “imminent threat” in the county because of the increase in recent detections. Over the past year, 25 wild animals, including raccoons and feral cats, have tested positive for the virus in Nassau County — a sharp increase since it was declared eradicated in the county in 2016. In March, Suffolk County also noted an increase in rabies in raccoons.

Rabies, nearly 100% fatal for humans, circulates in the wild animals around us. And while increases in rabies may sound scary, there are practical steps we can implement that make risk to humans pretty low.

What you can do

- Ensure that your pets are up to date on rabies vaccines — in New York, state law requires it. All New York counties offer free rabies vaccination clinics. For more information, contact your local health department.

- Do not touch or get close to wild animals, including feral cats. If you are bitten, immediately wash the wound with soap and water and contact your medical provider. Advise children to immediately tell an adult if they are bitten or scratched by an animal.

- If you see a wild animal that doesn’t look well, or you encounter a dead animal, contact your local health department or 311 if you are in New York City. Rabies symptoms in animals include tiredness, confusion, difficulty moving, aggression, drooling, and chewing objects like wood, soil, or stones.

Getting vaccinated is crucial if a wild animal bites you. I learned that firsthand in college when a monkey bit me while I was traveling — and I’m thankful I got the shots.

Question grab bag: A reader asks, ‘What’s the risk of rabies from a dog bite? Do we treat bites from wild and domestic animals differently?’

Great question. When we talk about rabies in the United States, most of the risk surrounds wild animals, especially bats, raccoons, skunks, and foxes. Domestic dogs and cats can carry rabies, but it’s actually extremely rare in the United States. In New York, because vaccination is mandatory, rabies in domestic cats and dogs is nearly unheard of.

With that said, when a person is bitten by an animal, there are multiple factors that go into determining the best course of action for rabies treatment, including:

- Vaccination status of the animal (if known)

- Type of animal (wild vs. domestic)

- Location of the bite: Bites to the head or neck or deeper bites can increase risk because they are closer to the central nervous system

- If the animal can be quarantined and observed for illness

- Local rabies levels and alerts (some areas have more local circulation)

The bottom line is that whenever someone is bitten by an animal, they need to contact a medical provider and public health as soon as possible to discuss the best course of action.

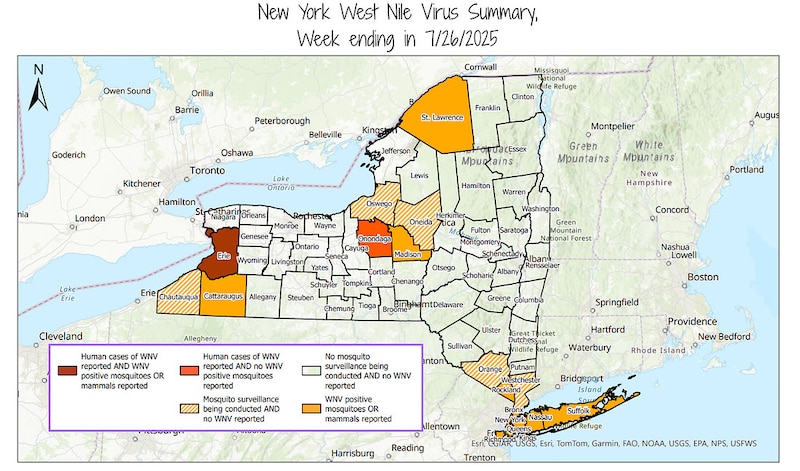

West Nile virus increasing in Long Island and rest of state

West Nile virus continues to heat up this summer with more mosquito detections across the state and in New York City.

Now is the time to be wearing mosquito repellent at dawn and dusk, or consider wearing long sleeves if it’s not too hot. Annoyingly, I had a mosquito fly into my loose pants last week and bite me on the shins, so I’m switching to repellent. Also, dump standing water around your home — it’s the perfect breeding habitat for these pests.

Bottom line

You’re all caught up! See you next week. :)

Love,

Your New York Epi

Dr. Marisa Donnelly, PhD, is an epidemiologist, science communicator, and public health advocate. She specializes in infectious diseases, outbreak response, and emerging health threats. She has led multiple outbreak investigations at the California Department of Public Health and served as an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Donnelly is also an epidemiologist at Biobot Analytics, where she works at the forefront of wastewater-based disease surveillance.