This article originally appeared at Your Local Epidemiologist New York. Sign up for the YLE NY newsletter here. Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

From debates on health insurance subsidies and innovations in patient care during outbreaks, to rising concerns of mosquito-borne diseases, a lot is unfolding in public health. Let’s unpack what it means for New Yorkers.

Infectious disease ‘weather report’

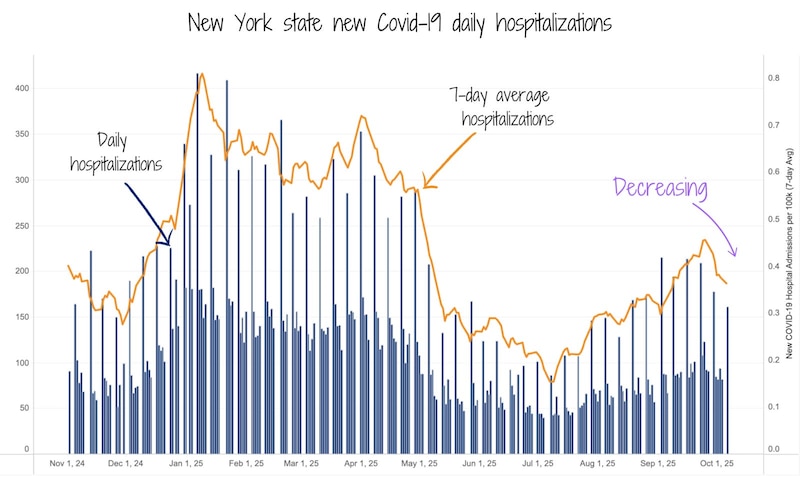

Covid: All New York wastewater data are delayed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dashboard isn’t updating during the federal government shutdown, the state dashboard paused reporting due to a lab transition, and New York City’s data download hasn’t been refreshed since July. In short, our early warning system is offline.

Right now, hospitalizations, our best proxy, are trending down, which is good news. Hospitalizations lag community spread, so we are likely well on our way down the summer wave.

Flu: Flu reports haven’t kicked off yet, and with wastewater data paused, we’re relying on last week’s low activity. So far, no sign of an early start.

RSV: This is the one to watch. RSV season usually starts around now, but delayed CDC data means we don’t have as many signals to rely on. New York state will start publishing its weekly respiratory report soon (they always start in October), so that will give us insight. I expect cases to rise soon.

Now is still a great time to get your fall vaccines.

New York health insurance on the line

What the heck is going on?

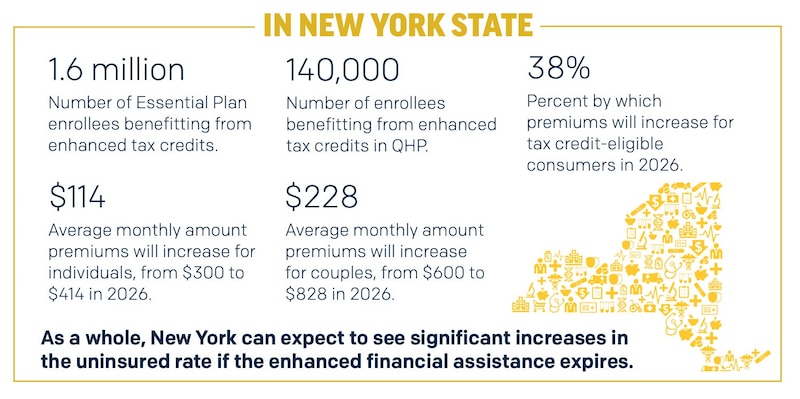

During the height of the pandemic, Congress passed temporary health insurance subsidies through the 2021 American Rescue Plan and extended them in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. These subsidies expanded eligibility for the Affordable Care Act plans and increased financial assistance for people with lower incomes. The goal was to make health insurance more accessible.

Now, Congress is debating whether to let those subsidies expire at the end of this year, or renew them. This decision has become a sticking point in federal budget negotiations and the subsequent federal shutdown.

How will this affect New Yorkers?

About 140,000 New Yorkers across the state currently benefit from these enhanced ACA subsidies. If they expire, those New Yorkers would pay an average of $114 per month for coverage.

Because these subsidies help lower income families afford insurance, any increase in cost could be a serious financial burden. This would likely result in more people delaying or dropping coverage altogether.

When fewer people have health insurance, health problems are more likely to go untreated until they become emergencies. This is more expensive for everyone in the long run — treatment costs more for individuals, hospitals, and the health system.

Why would we ever reduce health insurance subsidies?

Simply put, to cut costs. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that extending ACA subsidies would increase the federal deficit by $350 billion over the next decade. But, they would also keep coverage for about 3.8 million Americans who might otherwise lose it.

It’s a tradeoff: shorter-term budget savings versus long-term health.

My take

It would be a mistake to let these subsidies expire. While it may look like big budget savings on paper, the reality is that it will shift costs elsewhere, including to local hospitals, state budgets, and families already under financial burden.

When coverage becomes more expensive, many make tough decisions: delaying treatment, skipping preventative care, or forgoing insurance entirely. This can push illnesses to later, costlier stages — more late-stage cancers, unmanaged chronic conditions, and more infectious disease spreading in communities.

This isn’t just numbers. It hits real families who are already juggling to pay rent, buy food, and pay medical bills. I don’t see anything about this that leads to a healthier New York.

Reimagining patient care and safety during outbreaks

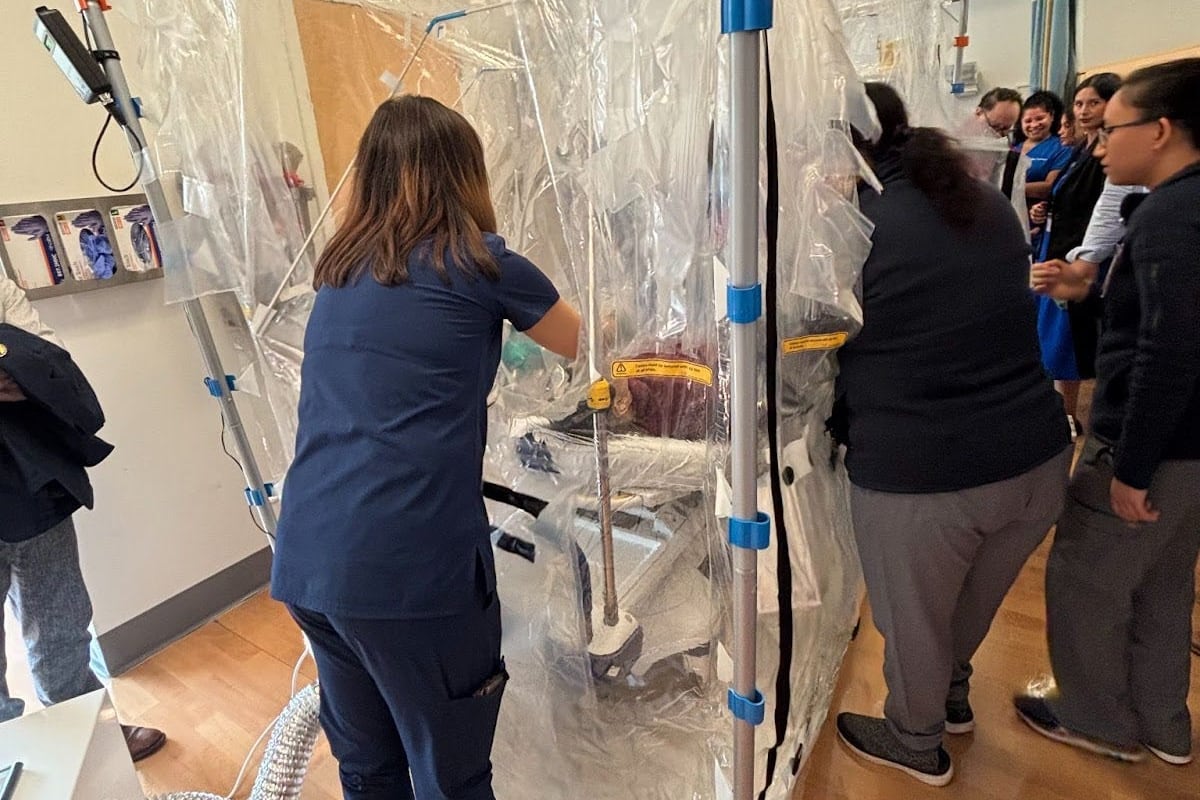

Recently, I visited a demonstration at NYC Health + Hospitals/South Brooklyn that reimagines how we protect both patients and providers during infectious disease outbreaks. At the center of it: a clear plastic containment chamber fully equipped with a hospital bed and monitors inside. Inside, a patient can receive care from clinicians who work through glove ports — similar to a neonatal incubator — without the need for full personal protective equipment.

The containment chamber is being piloted by doctors at NYC Health + Hospitals to determine if it’s feasible and worth investing in. In the image above, clinicians are running a simulation as if a patient potentially has MERS-CoV, a high-risk respiratory virus.

This setup has two big benefits:

- First, it dramatically reduces exposure risk for health care workers by fully enclosing the patient and their respiratory droplets.

- Second, it allows patients to see and be seen by loved ones — a stark contrast to the isolation we witnessed during the height of Covid, when loved ones couldn’t enter hospitals or patients’ rooms.

During the exercise, doctors and nurses performed routine care and even practiced an intubation through the chamber’s walls. They showed that, with training, complex procedures could still be done safely and efficiently.

It’s early days for this technology, and it won’t replace all infection control measures. But innovations like this are part of a growing toolkit that prepares us for future respiratory outbreaks, while maintaining human connection.

A big thank you to Dr. Syra Madad and the incredible team at NYC Health + Hospitals for their work, and for including me in this simulation.

Question grab bag

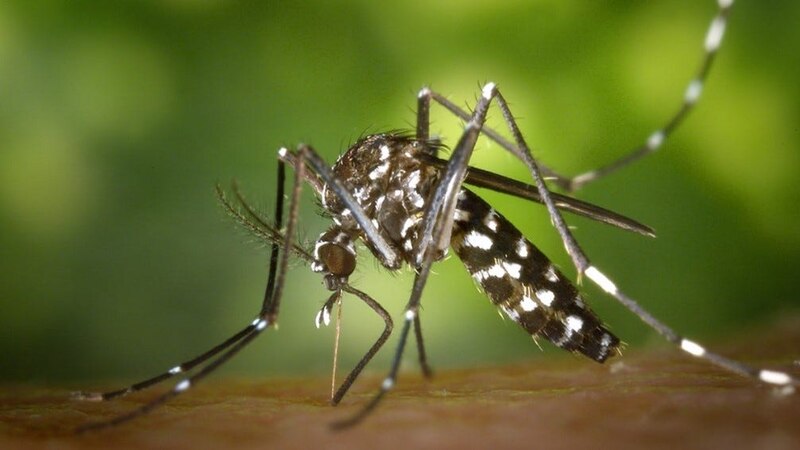

Will outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya, or malaria become more common in the United States?

Short answer: Probably yes, but only sporadically.

This goes back to the long history the United States has with mosquito-borne diseases. In the early 1900s, malaria was widespread across the country. It was such a huge problem that the CDC was founded in 1946 specifically to control it.

Dengue and yellow fever (spread by a different mosquito species), also caused outbreaks in the United States, mostly in the South. Through large-scale vector (i.e. mosquito) control programs — like draining wetlands, improving housing, and widespread insecticide use (including DDT, which was widely used at the time but is now banned in most countries because of environmental damage) — malaria, dengue, and yellow fever were all eliminated as a locally transmitted disease by the early 1950s.

Fast-forward to today. The mosquitoes that transmit malaria (Anopheles species) and dengue and yellow fever (Aedes aegypti) still live here, but the pathogens themselves rarely enter local populations. Occasional local cases, like the malaria in Florida, Texas, and Arkansas in 2023, remind us that vector control programs work well, but aren’t perfect.

For chikungunya, the primary vector (Aedes albopictus) arrived in the United States in the 1980s, through used tires imported from Asia. They’ve since spread widely across the Southeast and parts of the East Coast.

These mosquitoes are resilient. The mosquitoes that transmit dengue, yellow fever, and more recently Zika can breed in tiny amounts of standing water — think bottle caps, potted plants, or gutters — and thrive in warm, humid, urban environments. Vector control programs have slowed their spread but can’t eliminate them entirely.

For any outbreak to occur, four things need to align:

- The right mosquitoes must be present.

- The virus or parasite must be introduced (often by travelers).

- The climate must support mosquito survival and pathogen replication (the right temperature, humidity, and availability of standing water).

- People and mosquitoes must come into contact.

While vector control efforts are still in place to keep these pests at bay, climate change and international travel will make these conditions easier to occur in more places in the United States. This means that we’ll likely see more localized outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya, or malaria, especially in warmer states like Florida, Texas, and Arizona. But widespread, sustained transmission remains unlikely thanks to strong vector control and public health systems.

That said, we need to stay vigilant. The key is to continue investing in mosquito control and community prevention, like removing or treating standing water, mosquito surveillance and testing, and using repellents.

What else to know

Onondaga County is offering free naloxone (Narcan) training courses in person or over Zoom. Schedule it here.

Oneida County is giving a limited number of free car seats to eligible families on Oct. 21. Call 315-798-5461 or email carseatsafety@oneidacountyny.gov if you need a new car seat to see if you qualify.

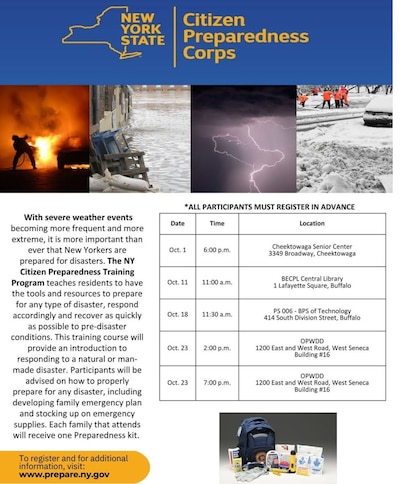

The New York Citizen Preparedness Training Program in Erie County is providing tools and resources to prepare for disasters, respond accordingly, and recover quickly. They have multiple workshops scheduled for October.

You’re all caught on this week’s New York public health news. I’ll see you next week!

Love,

Your NY Epi

Dr. Marisa Donnelly, PhD, is an epidemiologist, science communicator, and public health advocate. She specializes in infectious diseases, outbreak response, and emerging health threats. She has led multiple outbreak investigations at the California Department of Public Health and served as an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Donnelly is also an epidemiologist at Biobot Analytics, where she works at the forefront of wastewater-based disease surveillance.