Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

MedShare is a global health nonprofit founded in Atlanta in 1998. It sends medical supplies that are frequently discarded in the United States to clinics around the world for free. More recently, it has added domestic work to its portfolio, providing unique insights into the needs of American safety-net clinics that serve the most vulnerable.

Since its founding, the nonprofit has grown to work in 120 countries, including disaster zones, like Jamaica after Hurricane Melissa, and war-torn Ukraine. It ships items as small as sutures and syringes, to those as large as X-ray machines, transformers, and even, once, a morgue, around the world.

Now the organization is looking homeward, bringing its “circular approach” to medical supplies to American clinics that serve people in need, including in its home state of Georgia.

While the organization had periodically helped out in domestic crises like wildfires in California, CEO and Executive Director Stacey Koehnke told Healthbeat, Covid brought home the similarities between MedShare’s work abroad and domestic needs, since it had personal protective equipment to supply during the pandemic.

Since Covid, MedShare has adopted an intentional approach to working with clinics domestically. There are many similarities, she said.

Like the clinics it supports internationally, safety-net clinics in the United States serve vulnerable populations.

That domestic work has become a priority for MedShare over the past 18 months, Koehnke said, with 10% of its resources distributed domestically, with an eye toward further growth.

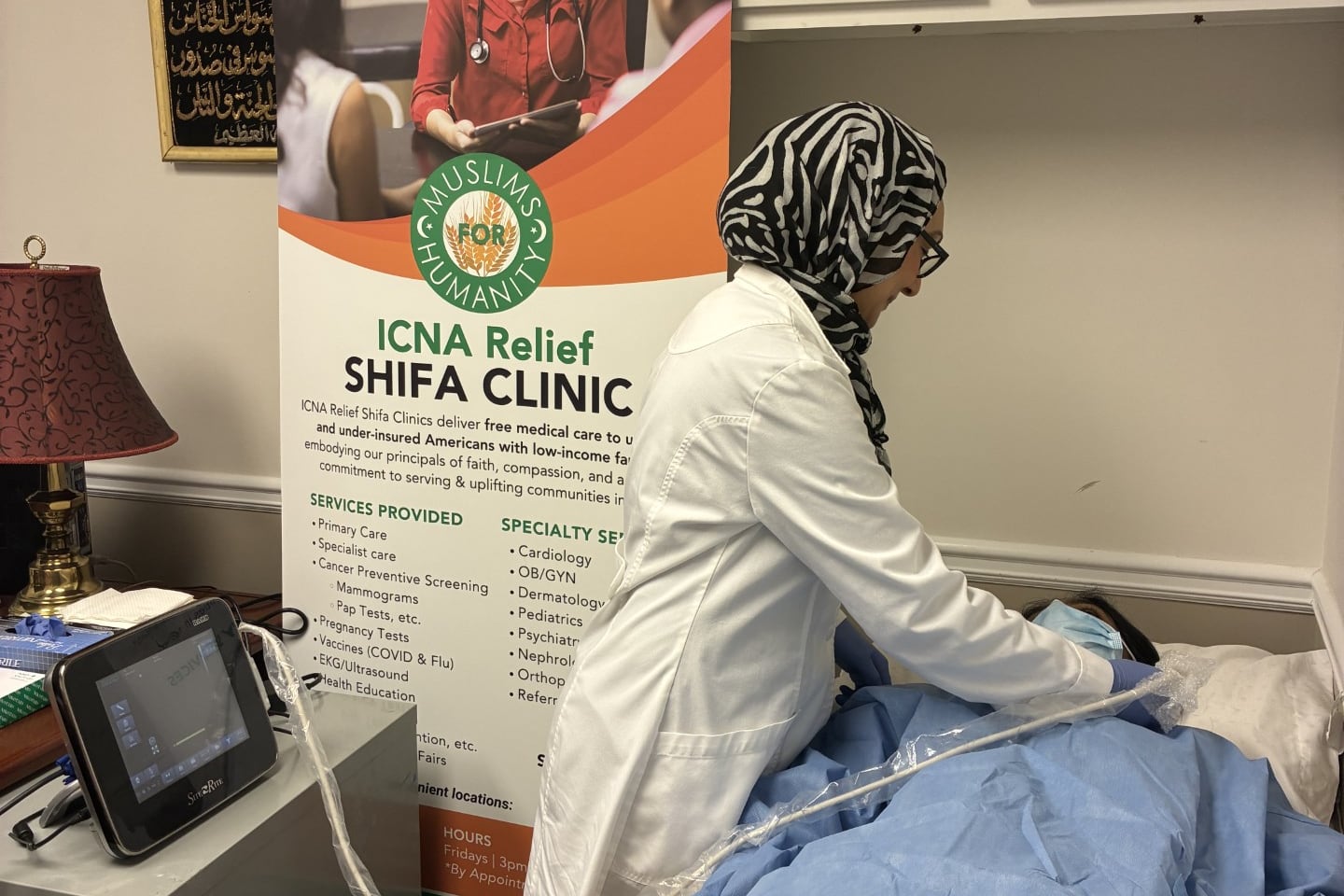

“Where our biggest impact is in access domestically for those communities who may be under- or uninsured,” she said, pointing to the examples of rural areas that lack hospitals, Native American reservations, and neighborhoods with many immigrants as other sites of health care need. MedShare has provided supplies to clinics in about 35 states, including at least 27 clinics in Georgia, in urban and rural areas.

Creative partnerships with medical supply companies help MedShare meet clinics’ needs at home or abroad. The goal is to provide needed supplies while preventing waste.

Take, for example, a recent effort to send ultrasound machines to low-cost clinics across the country. MedShare obtained machines from medtech firm BD. The equipment was new, but BD had taken the machines off the market in favor of updated models. MedShare sent the outdated but functional ultrasound machines to 30 states, Koehnke said. MedShare also provided training to technicians at those clinics in troubleshooting and using the equipment.

Patients can save money and time if they can get ultrasounds in clinics, rather than an outside provider, Koehnke said. That could help with maternal health and other issues, she said. MedShare also provides clinics with blood pressure monitors, both for patients with hypertension and for pregnant women who need to keep an eye out for pre-eclampsia.

Three of the clinics that got the ultrasound machines are in Georgia. Bethesda Community Clinic, based in Ball Ground in Cherokee County, will use one on a women’s health van to be deployed in the spring. The ultrasound machine will be used for basic prenatal care like confirming pregnancies and identifying complications early.

“Having this capability on our mobile unit allows us to bring essential diagnostic services directly to underserved patients who otherwise lack access to these resources,” said executive director Melissa Belfield. The free machine is helping the clinic expand its services without incurring costs that would take away from direct patient services.

The Macon Volunteer Clinic also got an ultrasound machine through the program, and the clinic’s nurse practitioner has attended a virtual training. The clinic plans to use it for placing IUDs and determining blood flow in cases of deep vein thrombosis, spokesperson Julia Norman said.

MedShare has in recent years focused on ensuring that the medical equipment it sends to clinics at home or abroad gets used over the long term by including training.

The domestic ultrasound donation program led MedShare to develop a remote training program since it couldn’t send team members to each of the American clinics that got the devices. It also sends its workers abroad to help clinic workers learn to use and maintain equipment.

“If there’s no one there who knows how to do basic troubleshooting and basic repairs, it becomes a wasteland of beautiful equipment that’s unusable,” Koehnke said.

Maternal care is a top concern, but it looks different in different places

Domestic work gives MedShare employees a close-up view of the challenges American safety-net clinics face.

One clinic that was using disposable tools was able to save money after MedShare provided it with an autoclave. The goal is to increase the resources that go to direct patient care instead of supplies, Koehnke said.

Decreasing federal and state funding is one concern, Koehnke said. The reduction of services or closure of community hospitals also puts added pressure on the clinics. She said many hospitals first eliminate maternity care due to liability risk, pushing the clinics to pick up the slack.

“We are seeing added requests, added needs for equipment that we originally didn’t know that we would need to provide,” she said. “We get requests for ultrasound all the time now. We don’t have as many ultrasounds to give as we’d love to.”

Maternal care is a concern domestically and globally, Koehnke said, but it looks different depending on the setting.

“We’re still working kind of within that (U.S.) system, so people are used to certain levels of care. There’s certain expectations from the different clinics and hospitals, and even the patients that we’re working with, which may have a different sensibility internationally,” she said.

For example, clinics abroad often want clean birthing kits, which help people deliver babies at home in sterile conditions. But that’s not the case in the United States. “That is not something we’d be able to provide domestically, even for mothers who may not have a hospital nearby.”

Koehnke said the needs are similar – pregnant women need to be prepared for safe births – but in the United States, the focus is more on preventing complications, such as through providing blood pressure monitors and pulse oximeters, the clip-on fingertip devices that measure heart rates and how well oxygen is moving through the body.

“It’s a different way to provide care, but the fact is that there are still underserved communities with families and children who need access to health care, and our role is to help ensure that those who can provide that direct care are given the tools and support to do that,” Koehnke said.

How MedShare works: It’s like Amazon – but free

Equipment comes to MedShare in a variety of ways, Koehnke said. Along with donations of equipment that is no longer for sale or has been refurbished, hospitals often have a large amount of everyday supplies like syringes that would otherwise go to waste.

She gave the example of a case of individually packaged syringes that a hospital or home health care facility would otherwise dispose of once it was opened, even though the remaining syringes were safe to use.

“We’re able to repackage those and get them actually out to someone who can still use them. So there is also a very much an underlying environmental element to the work that we do,” Koehnke said.

Nurses are often key catalysts for the donations, she said: “They’re thinking, ‘Wow, I really don’t want to throw this out. How can I get this to someone?’” Supply chain administrators at hospitals are also key conduits.

Once the supplies reach MedShare, it operates like most online shopping. Clinics register with MedShare and, once approved, they use an online portal to look for supplies. All supplies are free, and clinics outside Georgia pay only shipping costs, while Georgia clinics do not pay for shipping.

Rebecca Grapevine is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Rebecca at rgrapevine@healthbeat.org.