This article originally appeared at Your Local Epidemiologist New York. Sign up for the YLE NY newsletter here. Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

We’ll dive into the warm temperatures on New York’s radar, but first …

Have you voted yet? Last week, I shared a health voter guide for the NYC mayoral election. This week, I sat down with WNYC’s Brian Lehrer to discuss it. You can listen to our conversation here.

Okay, back to our scheduled programming …

Last weekend, I joined 9,999 other women to run a loop through Central Park for the Women’s Mini 10K. It was empowering and energizing, but wow was I struggling with the heat. I assumed the temperature must be in the 90s. The reality? Just 75°F.

The problem wasn’t the heat alone, it was the humidity. When moisture in the air is high, your body can’t cool itself as effectively. Sweat just sits on your skin instead of evaporating, making it feel much hotter than it is.

Next week, parts of New York could see high temps reach 100°F — the hottest day of the year so far. Because our bodies gradually adapt to heat as the summer progresses, we’re especially vulnerable in June. Early-season heat hits harder. There’s also truth to the old saying: It’s not the heat, it’s the humidity.

Let’s break down why heat and humidity matter — and what you can do to stay safe.

⚠️[Increasing Heat and Humidity!]: For early next week, we are looking at our first stretch of prolonged hot, humid weather beginning Sunday and lasting through at least the middle of next week. Stay tuned for forecast updates as we get closer at https://t.co/wTqdsomHTB pic.twitter.com/F7gU29rkQZ

— NWS New York NY (@NWSNewYorkNY) June 17, 2025

Back up: Why humidity feels so brutal

When it’s hot outside and/or we’re exerting ourselves, the body tries to cool itself down by sweating. But it’s not sweat alone that cools you down. The sweat needs to evaporate off your skin. The evaporation of a teaspoon of sweat could cool your entire bloodstream by 2 degrees F.

This is where humidity comes in. When there’s a lot of moisture already in the air, sweat can’t evaporate as effectively because the air can’t absorb more moisture, making it harder to cool down. The body’s cooling processes become less effective, and heat and humidity can become dangerous. Older people are more vulnerable to humid conditions because the body produces less sweat as we age.

Humidity and dew point describe how muggy it feels, but they measure different things:

- Relative humidity — the percentage in your weather app — tells us how full the air is with water vapor relative to its capacity. But warm air holds more water, meaning 60% humidity on a hot day feels much stickier than 60% on a cool day.

- Dew point is more precise. It measures the actual amount of moisture in the air. Technically, it’s the temperature at which air becomes saturated and dew forms. The higher the dew point, the more moisture is in the air, and the muggier it feels.

In short: The dew point is a better indicator. A dew point above 65°F feels sticky. Above 70°F, it becomes more uncomfortable and risky during a heat wave.

When I was running my race last weekend, the humidity hovered around 80%, with a dew point of 70°F.

Heat-related illness in New York

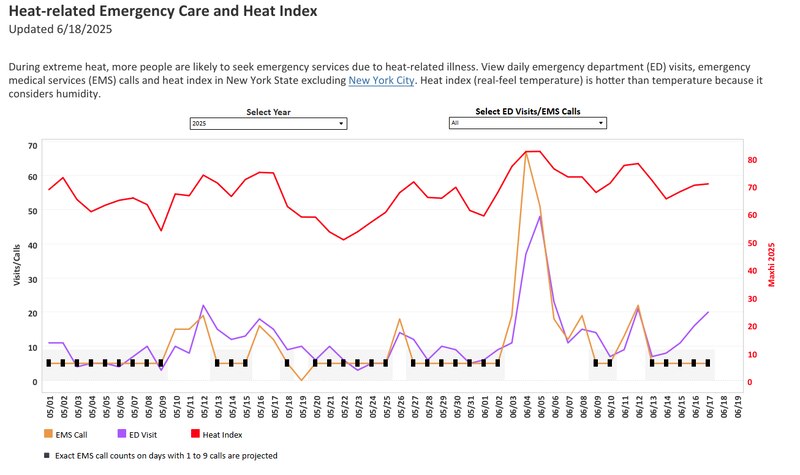

Every year, thousands of people across New York visit the emergency department for heat-related illness. In 2024, there were 3,213 heat-related emergency department visits in New York state, excluding New York City. From May 1, 2025, through Thursday, there have been 556 ED visits for heat in New York state (excluding New York City).

Heat illness can be severe. In New York City last year, seven people died directly because of heat, and 570 died because heat exacerbated underlying conditions, like heart disease. Those age 60 and over are most susceptible to heat-related illness.

Counterintuitively, people in New York who died from heat stress were most often exposed to dangerous heat inside their homes, not outside. Without air conditioning, indoor temperatures can be much higher than outdoors, especially at night, and can continue for days after a heat wave.

New York families with low incomes can apply for free AC units or fans through the Home Energy Assistance Program. In 2024, more than 25,000 households in New York state got access to cooling units through HEAP.

What you can do

The best thing to do is to try to stay cool and check in on neighbors who may not have air conditioning.

- Know your risks. The Centers for Disease Control and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration dashboard tracks local heat risk scores that takes into account temperature, humidity, and other metrics that impact health. The risk score ranges daily from “No risk” to “Extreme” heat risk. Enter your ZIP code here.

- Apply to get a free air conditioner or fan through HEAP, if you qualify. However, the future of HEAP’s program is uncertain. In April, all federal employees overseeing the national program that funds state-level HEAPs were laid off, and funds were frozen due to cuts at the Department of Health and Human Services. Applications will remain open only as long as state funds last — once they run out, no more households will receive cooling assistance.

- Use a cooling space. Cooling centers can be found in New York City here and across the rest of the state here. Libraries, museums, or coffee shops are great options.

- Keep your pets cool. They’re susceptible to heatstroke, too. Here are hot-weather safety tips for pets.

- Watch out for hot playgrounds. Metal, turf, and black asphalt can cause burns on hot days.

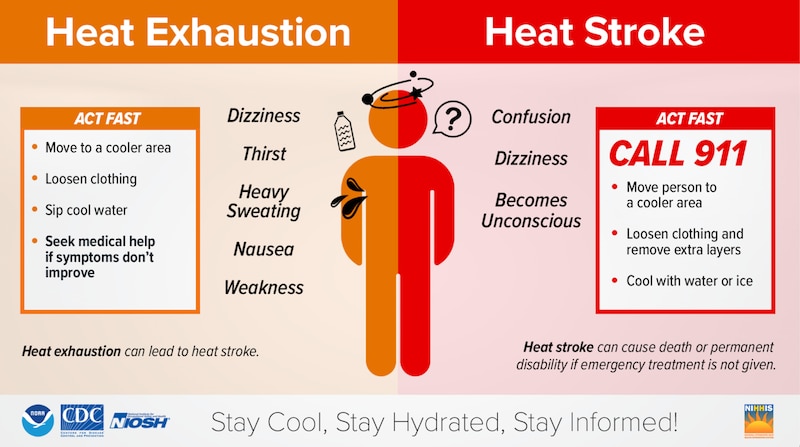

- Know what symptoms to look out for. Confusion, dizziness, and unconsciousness are serious signs of heatstroke that warrant calling 911.

Bottom line

It’s going to be a hot one. Stay hydrated, check on your neighbors, and don’t underestimate June heat — it can hit harder than we expect.

Love,

Your NY Epi

Dr. Marisa Donnelly, PhD, is an epidemiologist, science communicator, and public health advocate. She specializes in infectious diseases, outbreak response, and emerging health threats. She has led multiple outbreak investigations at the California Department of Public Health and served as an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Donnelly is also an epidemiologist at Biobot Analytics, where she works at the forefront of wastewater-based disease surveillance.