This story was part of Healthbeat’s live storytelling event, “Aha Moments in Public Health,” held Nov. 3 at Manuel’s Tavern in Atlanta. Watch the full show here. Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

The downstream echo of my “aha” moment in public health is the reason I was late arriving for tonight’s program.

Here’s the background. In 1981, Dr. Jim Curran led the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention task force that investigated the very first cases of a new disease that we all later came to know as AIDS. I joined the field as an AIDS community and medical educator five years later, and 12 years after that, in 1998, I was recruited from the Emory School of Medicine to the Rollins School of Public Health by Curran, who was by then serving as the school’s dean, to help him start a National Institutes of Health-funded Center for AIDS Research at Emory.

At one of our first meetings with organizational shareholders from across campus, someone floated an idea that CFAR and the Emory Vaccine Center could collaborate on hosting an evening seminar series to raise our mutual profiles.

“That’s a great idea!,” I chirped up. “We could serve food too and call it the Vaccine Dinner Club!”

Instantly the room erupted with laughter, but as soon as Curran handed me the job of designing, organizing, and running the new initiative, that is exactly what I did.

Having been told that a seminar on HIV vaccines at Emory might draw as many as 30 or 40 scientists, I booked an appropriately sized room and sent out an email to a couple of colleagues asking for their help in advertising our first gathering. In that email, which I begged recipients to treat like a chain letter, I asked people to write me back directly if they wanted to attend the VDC’s first meeting, which would begin with networking over wine and cheese, followed by a science presentation given by Emory Vaccine Center Director Dr. Rafi Ahmed, and end with a casual buffet dinner.

Return emails began to trickle and then pour in. This shouldn’t have been all that surprising because this was during a period in history in which you weren’t allowed to even serve coffee at a federally funded meeting, and here I was offering free wine, cheese, and dinner. But I was still floored when, by the time the Vaccine Dinner Club met for the first time a month later, on Jan. 6, 1999, more than 300 people had registered to attend.

As you may know, the CDC is a separate nation-state located on the Emory campus and, to this day, I swear I felt the ground rumbling gently beneath my feet as wave after wave of CDC employees came thundering down Clifton Road on foot, apparently at a dead run, in the direction of food-and-drink-enabled science.

My gratification turned to panic, though, when it became clear to the milling crowd that somebody (OK, me) had forgotten that wine bottles must be opened before their contents can be consumed.

Fortunately, it turns out that the VDC membership has self-selected for resourcefulness from the very beginning and that a surprisingly large number of people carry corkscrews in their pockets and purses.

In almost no time at all, an impromptu bucket brigade of meeting attendees, led by biostatistics luminary Dr. Betz Halloran, formed to uncrate, open, pour, and distribute 300+ glasses of wine. The rest of the evening was fabulous as well, and I really think that that night set the stage for thinking of the VDC truly as a club, not a seminar series.

But, believe it or not, that wasn’t my “aha” moment.

And it still wasn’t my “aha” moment 21 years and almost 200 programs later when the pandemic happened and the VDC had to go online.

Taking dinner club to Zoom opened it to more people

I still vividly remember stepping up to the podium on March 4, 2020, to open what later turned out to be our last in-person meeting for four years. The talk was titled Covid-19: What We Know, What We Suspect, What We Fear and starred Dr. Jay Butler, deputy director for infectious diseases at the CDC.

In those days, the VDC’s average meeting attendance was around 200, but I have no idea how many people were there that night. Seriously, I don’t because to maintain plausible deniability with the fire marshal I stopped counting at 550. But let’s just say that we were in a two-level auditorium and it was standing room only.

When I stepped behind the podium and looked at that absolute sea of faces, I put down the meeting-opening cowbell I had been ringing and, without thinking, blurted out:

“Dr. Butler’s talk will include an analysis of Covid-19 super-spreader events. And speaking of super-spreader events ... would everyone in this extremely crowded, windowless room please behave responsibly and hold your breath for the next 60 minutes?”

But my “aha, this is why I do it” moment didn’t even occur then. That came later, after the VDC had entered the Zoom era and my fear that the club would collapse in the absence of free wine proved to be unfounded. In fact, to my puzzlement, membership requests and registration attendance absolutely exploded in size during the pandemic to the point that I began opening each meeting with a slide showing the ever growing list of countries around the world from which any given month’s attendees were Zooming in.

And then one day it all made sense. I was reading registration form comments for the upcoming meeting and one said “thank you, Thank You, THANK YOU Kimbi for keeping the VDC going. My job is to increase Covid vaccine uptake in a part of the country that believes Covid is a hoax. I absolutely LIVE for these monthly opportunities to relax and spend time, even if only online, with my tribe, The People Who Get It. The VDC makes me feel less alone.”

That was my “aha” moment. That was when I realized that for some people, maybe many, attending VDC meetings was no longer simply about having access to cool science, it was now also, and perhaps more importantly, about having access to a safe space where — in a world that was increasingly making the trashing of public health and public health professionals into a full-time job — they could feel seen, heard, supported, and not so alone.

Now there are two: Vaccine Dinner Club IRL and online

I am a public health professional like most of you here, but it turns out that my public is you — the people who make public health happen. I do what I do, so that you can do what you do.

That insight was re-crystalized for me post-pandemic when, after pausing the VDC for the entirety of the 2024-25 season, I was absolutely inundated with hundreds of thank you messages when I restarted the club this past September.

As a result, when the VDC’s two major sponsors notified me that they want VDC meetings to scale back from monthly to quarterly and revert to in-person only, which would restrict meeting attendance to people in Atlanta, I became acutely aware of the sense of abandonment and exclusion that that might create among the membership.

My solution was to start a second club. With sponsorship from the Rollins School of Public Health, the new club only meets in the months that the Vaccine Dinner Club does not meet and addresses public health issues that are not vaccine specific.

Because I outsourced the naming of the club to the members and we are currently narrowing down possibilities for a final vote, the new org is currently officially known as the As-Yet-Unnamed Dinner Club, or UDC. Membership in the UDC, which didn’t even exist 2 months ago, is 6,711, which is almost 1,300 more members than the Vaccine Dinner Club took 27 years to accrue. That speaks very strongly about the continued need for an organization like this.

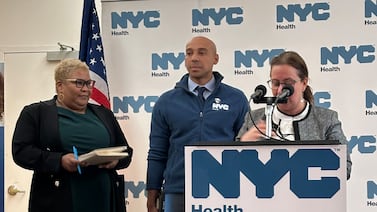

Our inaugural meeting of the As-Yet-Unnamed Dinner Club on Oct. 1 was titled Public Health Chaos: What It Means for America, and starred three long-time VDC members, Drs. Demetre Daskalakis, Deb Houry, and Dan Jernigan — aka “D3” — the three senior leaders who resigned from the CDC after Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. fired CDC Director Susan Monarez.

Almost 2,600 people attended that first meeting, including more than 100 who have retroactively registered after the meeting was over, just to receive a link to meeting recording.

The second meeting of the UDC, Science Under Siege: What You Can Do About It, took place this evening. It featured superstar author Dr. Peter Hotez and is why I was late getting here tonight. Because I couldn’t bear the thought of missing out on your stories, not to mention Healthbeat’s first birthday party, I hosted this month’s UDC meeting from my laptop here at Manuel’s Tavern. You can retroactively register for that meeting if you want to hear Hotez’s thoughts about how we can fight anti-science.

Why there’s hope for public health in America

Speaking of anti-science … before ending my story, I want to read a few sentences that I included in my email opening registration for this evening’s UDC meeting. They originally came from an email to one of the UDC members and spring from conversations I have been having with multiple VDC and UDC members who have reached out to talk about how distraught they are, as I am, as we all are, over the deliberate damage that is being done to public health in America right now. This is what I wrote:

“I keep reminding myself that perhaps the only advantage to being as old as I am is that I have lived a long time. Including growing up in the Jim Crow South. Which means that I have real-time memories of cross burnings, segregated schools, whites-only everything, and the Tuskegee study.

“Which also means that I know, from my own lived experience, that we as a country are fully capable of righting great wrongs that are inflicted on us by our government because we have done so before. There is precedent for it in my own lifetime.

“So I have to believe that we will get through this because we can get through this because we have gotten through even worse. And successfully come out on the other side.”

Thank you.

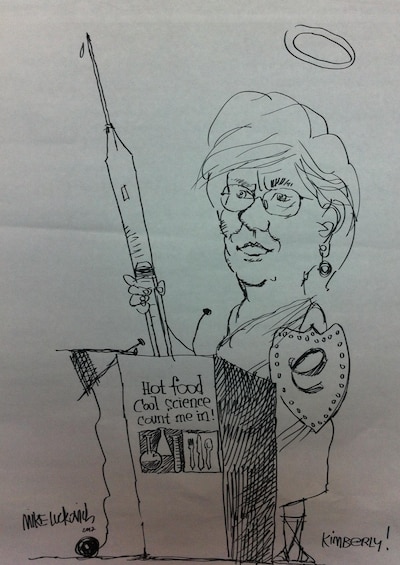

Dr. Kimbi Hagen is the founding director of two international science-focused dinner clubs. She has been a faculty member in the Department of Behavioral, Social, and Health Education Sciences at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory since 1998.