This story was part of Healthbeat’s live storytelling event, “Aha Moments in Public Health,” held Nov. 3 at Manuel’s Tavern in Atlanta. Watch the full show here. Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

Days after my 18th birthday, I had a seizure in a lecture hall of 300 people. My introduction to Clemson University and collegiate life involved an ER trip and a big unanswered question: What caused the seizure?

Afterward, my health began to decline. My heart was constantly racing out of control, and I would get dizzy and start sweating profusely, occasionally passing out. I was severely fatigued, and my body ached all over.

I bounced between specialists, had every test you can think of, and left each appointment with more questions than answers.

Then one night while scrolling through Twitter (as one does when they’re desperate for distraction), I came across a lab at the Medical University of South Carolina researching the mechanisms of hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, also known as hEDS, a genetic connective tissue disorder.

The collection of symptoms I was reading about sounded suspiciously like what I was living through. Not only was the team in Charleston conducting research, but they were looking for interns — interns who had hEDS.

Most primary care physicians are unfamiliar with hEDS. The average delay between symptom onset and diagnosis is over 10 years. On top of that, hEDS is the only subtype of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome that does not have testing available for known causal genes. That means it is both an “invisible disability” and an unsolved puzzle for the medical community.

I had no diagnosis at the time, but I reached out anyway. I asked if I could still apply, even though my condition had not been confirmed. After I interviewed, it took them just seven minutes to offer me the position.

That summer, I moved to Charleston. I spent my days doing research and learning about hEDS, and through the incredible mentors I met there, I finally got my diagnosis confirmed.

At the end of the summer, my mentor and the team sat me down for a meeting — not to discuss the data I was working with, but to persuade me to pursue a PhD. To consider research as a career.

After a whole year with no direction, no thoughts of anything past the day in front of me, I was suddenly imagining a future in science. I had previously intended to pursue genetic counseling, but the proximity of research to groundbreaking developments in the field drew me in.

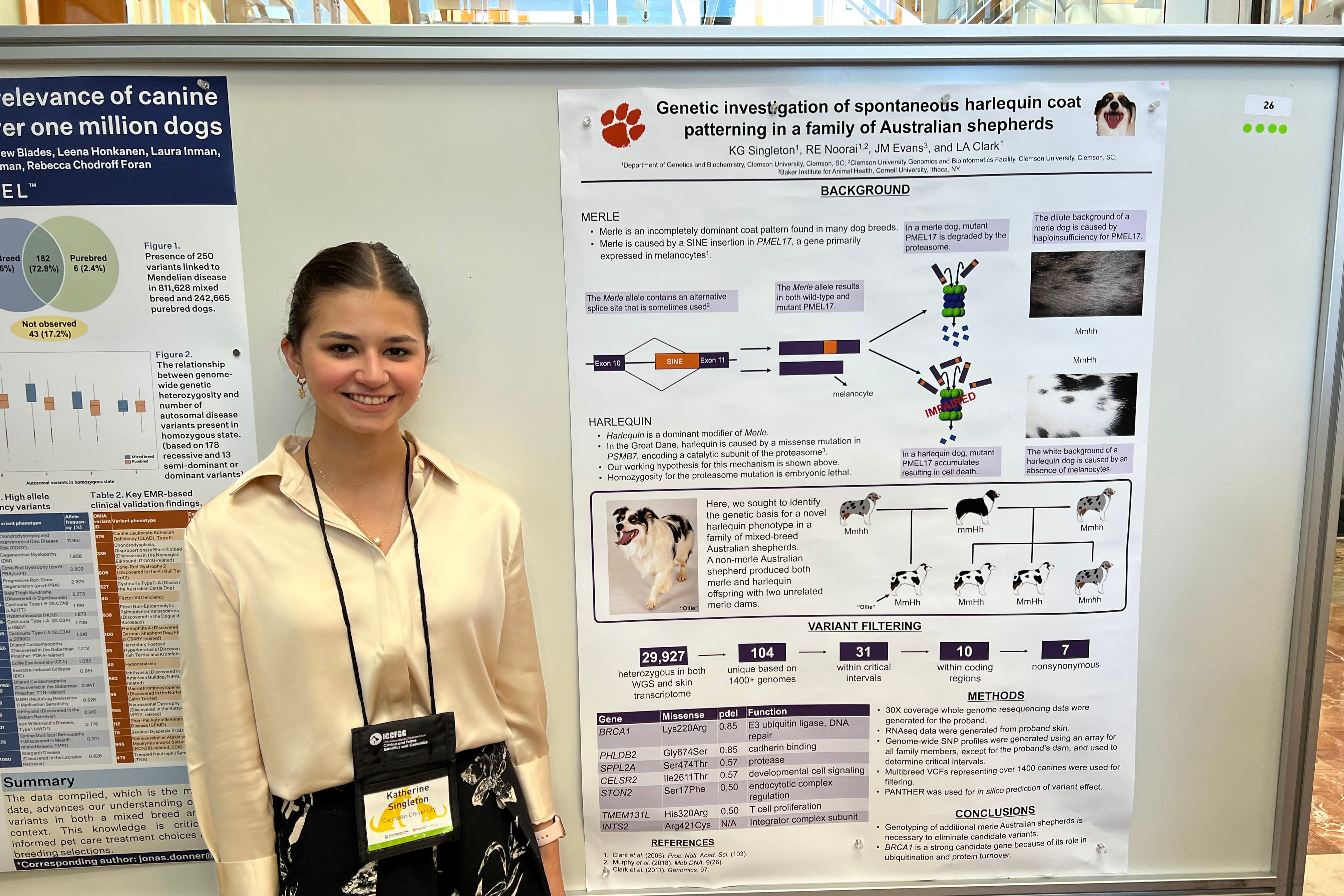

Back at Clemson, I switched my focus to research. I joined a canine genetics lab comparing disease etiology in dogs to what was known in humans. I started my own independent project on Miniature American Shepherds, fell in love with Eloise, and she is now my greatest joy.

When I applied to graduate schools, I was advised against disclosing my disability until after I received offers. It might be seen as a hindrance toward my degree progress and ability to produce research for a university. I decided to write about it anyway in my admissions essays because I didn’t want to attend a program with a culture that would not support disabled students.

I leaned into my story. I talked about my diagnosis, my lived experience, and my passion for accessible research. I wasn’t trying to hide my disability — I was reframing it as a strength. And it worked. I received offers of both admissions and fellowships, and I got to share my experience as a patient-scientist.

I think the programs that accepted me recognized that, having experienced the patient side of genetics, I can provide a valuable perspective and enhanced motivation to clinical research and patient care. Patients are an often overlooked resource for important scientific questions, and patient outreach can lay the groundwork for developing treatments and interventions that target the most troubling issues.

MUSC’s hEDS research program and the internship I participated in have led to the first candidate gene discovery, with almost every initiative driven by a patient-scientist.

We need more disabled representation in both genetics and biomedicine to provide an empathetic lens to our research and connect our goals back to those we hope to serve. By including patients and disabled researchers in the research that benefits them, we ensure the impact of our work and learn from the perspectives of those it supports.

Diverse perspectives in research broaden our minds, enhance our critical thinking, and keep moving us forward. Because inclusive science means better science — for everyone.

Katherine Grace Singleton is a genetics and molecular biology PhD candidate at Emory University. She is from Sumter, South Carolina, and did her undergraduate degree and research at Clemson University. After completion of a PhD, Katherine hopes to complete an ACMG-accredited Laboratory Genetics and Genomics fellowship program to continue research in a clinical setting.