This story was part of Healthbeat’s live storytelling event, “Aha Moments in Public Health,” held Nov. 3 at Manuel’s Tavern in Atlanta. Watch the full show here. Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

I’ve been working in addiction counseling for a long time. And every now and then, a story sticks with you. This one — this one stuck.

I had a client who was referred to us from another agency here in Atlanta. Homeless. Strong opioid addiction. He was getting Suboxone through a county program at 10 Park Place. That’s part of the Fulton County Health Department. He’d come in every couple of weeks to get his dose.

We kept his medication locked up — two locks, two keys. That’s how we do it. When clients are in treatment, they bring in a 30-day supply of whatever they’re on — blood pressure meds, HIV meds, mental health meds, you name it. We monitor it, make sure they take it right, and lock it back up.

This guy — he was from South Georgia. Used to climb trees for a living. Had a whole Facebook page full of pictures of him way up in the branches, cutting limbs like it was nothing. Strong guy. You could tell he’d worked hard his whole life.

But addiction doesn’t care how strong you are.

Word got back to me that he was selling his Suboxone – that’s a medication used to treat opioid use disorder. Or maybe overusing it. Either way, I had to let him go out to get it. That’s part of the process sometimes.

Then one day, he’s in my office. I’m sitting with a veteran client, and my guy is slumped over at the desk. I hear him snoring, but something’s off. I tell the vet, “Wake him up.” Still hadn’t hit me yet.

The vet nudges him — and he slides out of the chair.

I’m like, “Lord, he’s going into cardiac arrest.”

I jump into action. Start CPR. If you’ve never done CPR by yourself — it’s a workout. I’m on speakerphone with 911, rotating compressions with the vet, yelling down the hall for someone to bring me the defibrillator.

But there’s no one. No staff. No other clients. Just me and the vet.

Finally, the ambulance arrives. They revive him. He’s on the stretcher, heart monitors on his chest, and the first thing he says is: “Mr. Smith, you saved my life. I’m never doing dope again.”

I believed him. I wanted to believe him.

But maybe 10 days later, he’s back. High as a kite. Shirt off. Causing a commotion in the parking lot. It’s wintertime.

I go out to talk to him. I say, “What about what you told me? That I saved your life?”

He looks at me and says, “I don’t remember that.”

I said, “That’s okay. But I’m gonna have to ask you to leave the property. You can’t be out here half-naked, making a scene.”

That was the last time I saw him.

And here’s the thing — this isn’t rare. But addiction is a disease. It’s not a choice. It’s not a moral failure. It’s a cycle. And sometimes, even when you save someone’s life, they don’t remember. Or they’re not ready. Or they’re just too deep in it.

But we keep showing up. Because every person who walks through our doors deserves another chance.

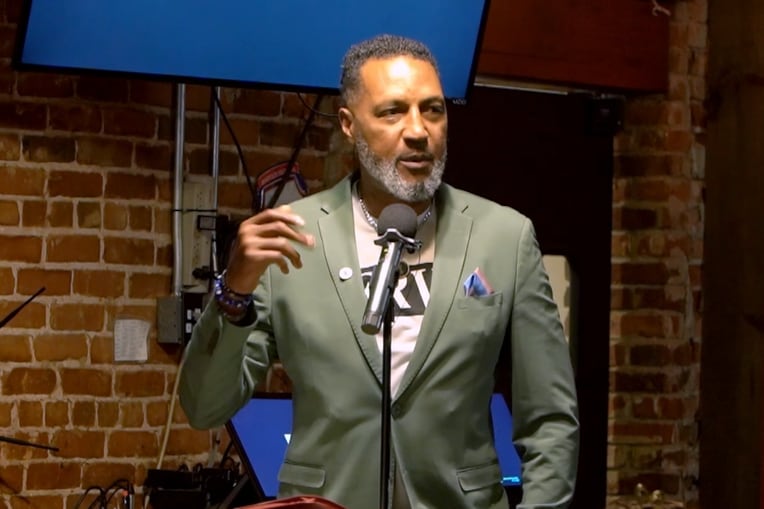

Johnny Smith is a certified addiction counselor and substance abuse case manager at Mercy Care, where he helps guide others through the same journey he once walked. A former top-ranked basketball player in Georgia and professional athlete overseas, his life took a dramatic turn due to addiction. After years of struggle, he found recovery at the Salvation Army, where he now also serves as a part-time chaplain.