Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

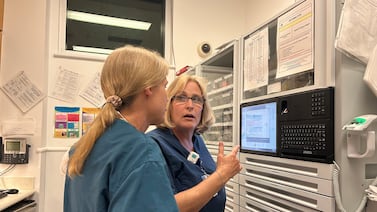

It can be tough for anyone to decide to get help for substance abuse, but nurses in Georgia face a special set of barriers: They have to report seeking treatment to the state’s Board of Nursing, which can jeopardize their license or put long-term restrictions on their practice and job prospects.

Addiction recovery and nursing advocates are urging the state to adopt an “alternative to discipline” for nurses who want to get help for substance use issues. The aim is to keep nurses in the workforce and ward off serious crises for them and their patients. At least 41 states have implemented such programs, according to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Georgia has not, though all five neighboring states have.

A bill to set up such a system came close to passing in the state legislature earlier this year. Sponsored by Rep. Ron Stephens, a Savannah Republican, the bill passed the House unanimously but failed to get a Senate floor vote.

Advocates plan to renew the push during the next session, which begins Jan. 12. The Board of Nursing will also consider the idea at its December meeting, a spokesperson for the board’s parent agency, the Secretary of State’s office, said.

It’s much needed, said Greg Gardner, a peer recovery coach for the Georgia Council for Recovery. He said that of 25 nurses struggling with alcohol use disorder he has seen in emergency rooms as part of a peer support program, only one was willing to proceed with getting help.

“They feel they will lose their license, they will lose their job, even without an incident at work. Moms with kids, they can’t afford to lose their job. They are terrified of what’s going to happen if they ask for help,” Gardner said during a Thursday meeting of the Georgia General Assembly’s Working Group on Addiction and Recovery.

In 2024, the board took 238 disciplinary actions for all reasons, according to data from the Secretary of State’s office. The board wouldn’t say how many were related to addiction, citing confidentiality. The Georgia Nursing Association sees 200 to 250 nurses in its Peer Assistance Program for those struggling with addiction, executive director Felicia Chatman told Healthbeat.

Seeking treatment triggers disciplinary process

As part of their license renewal process, nurses must check a box stating they have not sought treatment for substance use within the past five years, even if they’ve had no incidents at work, Gardner said. Colleagues or supervisors can also report nurses, and nurses can choose to self-report as well.

Such reports, whether through the license renewal process or another way, trigger a disciplinary process with the state Board of Nursing – and can deter nurses from seeking help.

The reports typically result in a “consent order” that establishes steps nurses must take to maintain their license and continue to practice. That includes regular drug tests and participation in recovery support programs.

The details are public, and nurses may face difficulty finding employment even many years after completing all the steps and remaining sober because of the disciplinary record, several nurses told Healthbeat.

The initial process can take up to a year or 18 months to play out, during which time a nurse might move to another job or face worsening addiction, said Helen Diana Ware, a registered nurse in recovery who spoke during the Thursday meeting.

“That’s not protecting the public,” Ware said.

The formal disciplinary process isn’t foolproof, Alison Trinkoff, a nursing professor of the University of Maryland-Baltimore who studies nurses’ well-being and substance use, said in an interview. She added that some employers may fire nurses without reporting them to nursing boards.

Advocates say alternative system could head off more serious problems

Ware and others said providing an alternative to discipline would encourage nurses to get help before their problems become more serious or endanger patient safety.

“When they enter our program, they really do run into barriers with re-entry and finding employment because they have a consent order,” Chatman said. “The irony … is that those are the nurses that employers can hire that are really the safest nurses out there, because they’re being monitored” with routine drug and alcohol testing.

Chatman and others at the Peer Assistance Program want to see the state adopt the alternative-to-discipline program.

“Those nurses that … know that they’re getting into trouble, they’re not healthy. They want to get treatment. They can reach out to us and say, ‘Help, help. Yes, my house is not on fire yet. I’m not arrested. I haven’t stole drugs, and I don’t want to go down that path of destruction,’” said Barbara Austin, a nurse who helps facilitate recovery meetings through the Peer Assistance Program.

“It would be a phenomenal boost, not only to the nursing shortage, but to the health of nurses in Georgia,” Austin said. About 153,544 nurses worked in Georgia in 2024, and the state is short an average of 772 RNs each year, according to the Georgia Center for Nursing Excellence.

“We need every nurse we can get,” said Mary Lou Wilson, an administrator at the Northeast Georgia Health System.

Alternative to discipline programs are generally effective, Trinkoff said.

“It gives you options as a nurse. ‘Hey, I can hang onto my license. I can get better,’” Trinkoff said. “‘This is good. I don’t have to worry I’m going to be a danger to myself and to others.’”

Rebecca Grapevine is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Rebecca at rgrapevine@healthbeat.org.