Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

Frontline HIV prevention advocates from across the South gathered in Atlanta over the weekend to collaborate and compare notes about how to respond to challenges created by funding cuts and new Trump administration policies.

At the Saving Ourselves Symposium, an annual conference for leaders of color working on HIV prevention in the South, attendees were particularly alarmed about federal attempts to block projects that focus on gender identity and the health needs of the communities they serve.

Participants raised concerns about their ability to continue work on testing, education, and disease prevention – and about their own mental health as they navigate the challenges.

Trump’s proposed budget for next fiscal year would dramatically reduce funding for HIV prevention, and funding clawbacks have impacted organizations working on vaccine equity with vulnerable groups and people of color.

Here are four takeaways from the conference, which was themed “Black to the Future.”

HIV advocates worried about impact of funding and policy changes

The threat of funding cuts and the changed political environment were at the top of the agenda for many at the conference. Even groups that have not yet lost funding are rethinking their strategies as they anticipate cuts.

“It’s much harder now, as an organization. We did not immediately lose any funding, but what we did do was immediately began to forecast, and we know that it’s happening now,” said Kevin Anderson, CEO of the Houston-based The T.R.U.T.H. Project. “It just doesn’t look the same.”

Many leaders from different states said cuts that impact their work could come from a variety of directions.

For example, FreeState Justice, a Maryland LGBTQ+ advocacy group, lost state funding for a project involving victim services for people impacted by crimes, including hate crimes, Executive Director Phillip Westry said.

The latest funding problems are compounded by the longstanding structure of how HIV services are funded in the United States. Community groups are typically asked, as a condition of funding, to test or link to care for a certain number of people. That can lead to competition among groups to provide services to the same small group of clients in a certain region.

In response to those concerns, Daniel Driffin urged leaders to find ways to work together and to focus on their broader impact rather than just the raw numbers. Driffin is a project manager at the HIV Vaccine Trials Network and longtime HIV prevention advocate in Atlanta.

The conference drew a smaller number of people this year, about 156, compared to last year, said Mardrequs Harris, deputy director of the Southern AIDS Coalition, which organized the event.

Transgender people – especially those of color – face particular challenges

An in-depth, community-led study of Black trans women in Houston found that many feel a loss of autonomy over their bodies and judgment due to longstanding discrimination and the Trump administration’s attempts to restrict trans people’s rights.

That can manifest in challenges in accessing health care, with Black trans women being asked unnecessary questions by medical providers and feeling judged by staff. They also face long wait times for medical appointments and prescriptions. The need to seek separate care for issues ranging from gender transitions to HIV to routine matters can compound the complications, the study found.

Black trans women want doctors to “treat my cough and not my gender,” said Joelle Espeut, the advocacy director at The Normal Anomaly Initiative who helped lead the study.

Organization leaders said they are feeling pressure to remove references to trans and gender non-conforming people from their official materials as they seek to protect their funding, creating a feeling of erasure.

Black trans women want to be included in the leadership of a variety of organizations, not just those focused on trans people, and be seen as regular members of society beyond just their gender identity.

“We work, we pay bills …. we are still taxpayers, we are still a part of this community,” said Christen “Coco” Valentine. “We’re human. So cut the stigma out.”

HIV workers focus on resilience

Many conference attendees said the recent funding cuts have taken an emotional toll on them.

“We’re holding the insecurities, the disappointments, the frustrations, the erasure,” said Simone Phillips, director of training and technical assistance at the St. Louis HIV/STI Prevention Training Center. Her comments drew “amens” from the audience.

“All of these headlines are just flooding us with nos and nos. So it does make you pause. It does make you feel overwhelmed, but it’s also like almost powerless to the sense of, ‘where do I start when there are so many fires?’” said Brady Maiden, the community science program manager for the Southern AIDS Coalition.

The desire to tell a different kind of story, one focused on resilience, was the impetus for Anderson’s short documentary “And We Rest on Giants,” which focuses on the stories of long-term HIV survivors and attempts to highlight the “joy and resilience as individuals that were living and thriving with HIV.”

The goal of the film is to encourage people to have conversations about HIV with their families and communities, reduce the secrecy and silence, and show that people living with HIV have rich and fulfilling lives and are not defined by the disease.

Resilience includes envisioning new ways to connect and support others in their community – like a proposed “auntie circle” in Houston, where women can lean on each other and learn from older trans women, said Bec Sokha Keo, a researcher at the University of Houston who helped coordinate the study.

Community support can be a vital resource

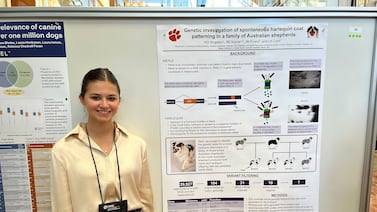

Research on HIV in the South can overcome federal funding cuts, Maiden said, by turning to community support, which can also help build trust and improve outcomes.

Research doesn’t always have to be sponsored by a large institution, Maiden said: “We are the subject matter of experts, and we’re allowed to ask questions.”

It’s important to ensure that projects center local voices because different parts of the South have different histories and challenges, she said. And it’s important to disseminate results of research to the communities who participated or are affected by the findings. Even decisions as basic as choosing a location should be guided by community needs and equity, she said.

“Community science is working with community, activating with community, being intentional, and making sure that we’re also using community to be the experts, but giving them that information back so they can also use it for what they need to advance,” Maiden said.

Rebecca Grapevine is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Rebecca at rgrapevine@healthbeat.org.