Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

The WIC program, which has provided healthy food, health care referrals, and breastfeeding support for women, infants, and young children for more than 50 years – historically receiving strong bipartisan support – came out of the fall federal government shutdown intact for another year. But New York City public health experts fear that President Donald Trump’s looming transformation of public assistance will have ripple effects that will still hamper WIC access.

“We are headed toward a very uncertain future,” said Jack Newton, who directs the Public Benefits Unit in the Bronx office of Legal Services New York, helping people obtain and retain public benefits. “The next two years will be a sea change among low-income New Yorkers, who will find a dramatic change for nutrition assistance and health care.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that about 6.7 million people received monthly WIC benefits, including about 41% of all infants nationwide. That same year, 233,703 New Yorkers relied on WIC each month – over half of the state’s total beneficiaries, according to the New York State Comptroller.

On a typical day at a WIC agency in New York City, parents and their children come in for a health check, breastfeeding advice, or a nutrition consultation. They come to get referrals to prenatal or pediatric health care. They might also refill their eWIC benefit cards they can use to purchase healthy food and baby formula for a few months. Often they get help enrolling in other public assistance programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly known as food stamps), the Head Start early education program, Healthy Start, or Medicaid.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, WIC services have increasingly moved to remote access, allowing families to avoid taking time off work or organizing child care to keep their required appointments. Yet, throughout the country, and across New York City, local clinic offices, rooted in their communities, remain a key feature of the program.

When the federal government shut down on Oct. 1, unable to pass a budget for fiscal year 2026, WIC recipients and providers worried about how long the local agencies could remain open, and what changes might occur in the short term. Concern ran parallel to fears about SNAP benefits, which were disrupted in early November, delayed and debated in court, and finally distributed to New Yorkers on Nov. 9.

Each new day of the shutdown brought new, often conflicting information. Several states, including New York, jumped in to cover a looming funding lapse with their own budgets. The USDA moved money around to cover WIC benefits. The White House injected emergency funds. Most WIC clinic managers in New York proceeded with a precarious “business as usual,” taking one day at a time and keeping a low profile.

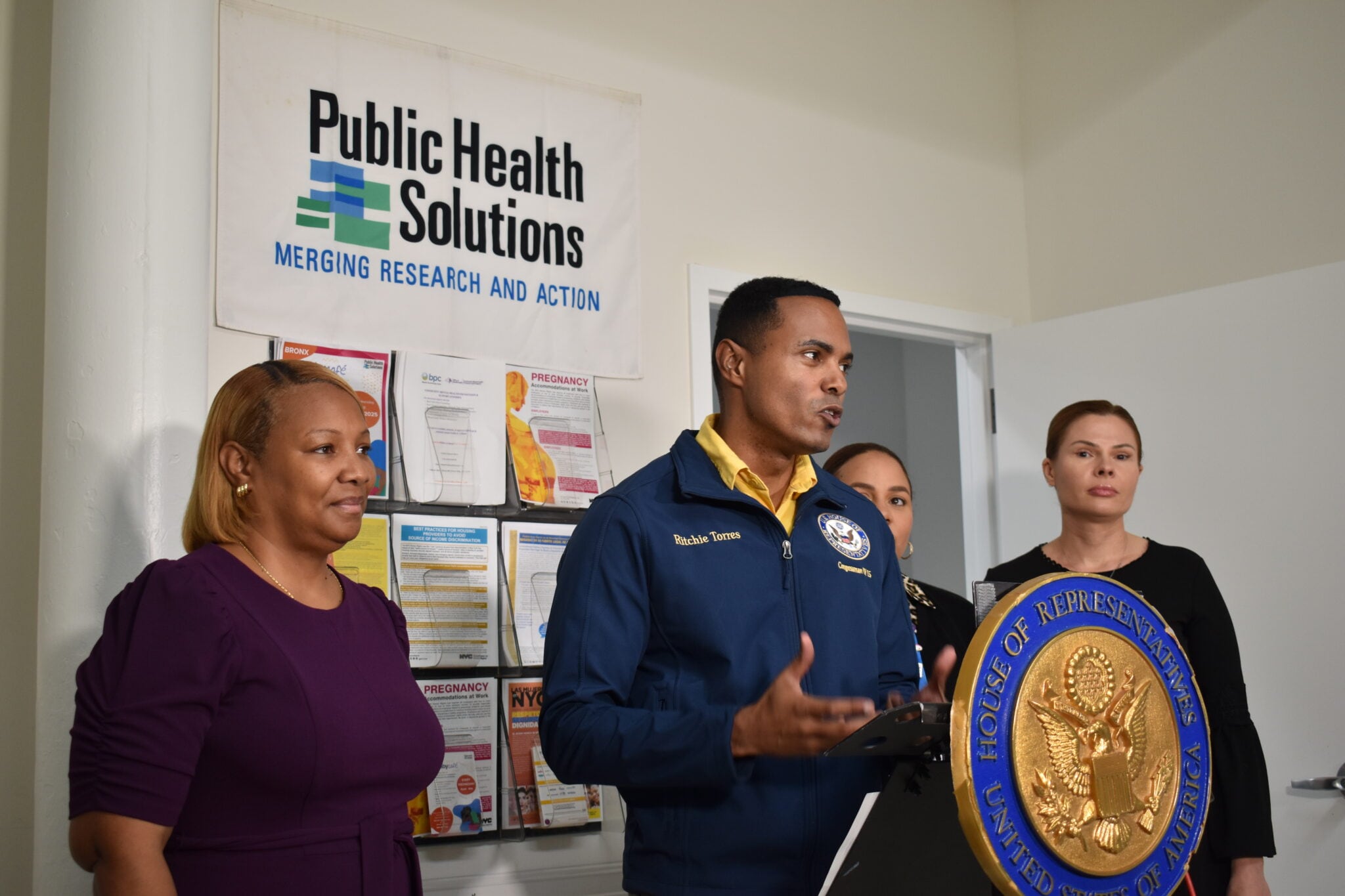

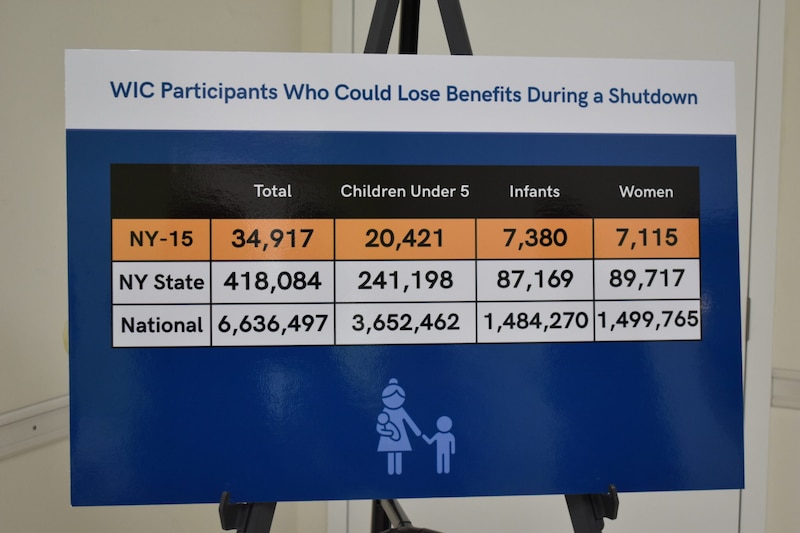

As New York state’s largest WIC Vendor Management Program and WIC provider, Public Health Solutions, however, quickly took a vocal stance. On Oct. 8, leaders of the non-profit organization gathered for a press conference at their WIC office in the Bronx with Democratic U.S. Rep. Ritchie Torres. Speakers highlighted the urgency of the situation – and the consequences of a sudden lapse in or loss of WIC benefits for the 35,000 low-income women, infants, and children that PHS annually serves through their WIC program.

For the Bronx, Torres said, WIC is essential.

“My congressional district is the largest recipient of WIC of any congressional district in New York state,” Torres said. On that day, he was speaking “not only as a United States congressman, but as the product of a strong single mother, who raised my twin brother and me on the strength of the WIC program.”

PHS was responding to the immediate crisis. But concern about the future of WIC had begun before the shutdown, and remains top of mind for many recipients and advocates, despite the funding deal’s reprieve.

The recurring, principal concern is that social benefits are not designed as isolated forms of support – they work together. Changes to one part of the system, the non-profit National WIC Association explains, will not be contained. Changes in other programs to eligibility criteria, new work requirements, enrollment procedures, cost-shifting onto the states, and, now, a potential expansion of the nation’s “public charge” determination means fewer people might access WIC.

Many recipients of public assistance have been anticipating those ripple effects, Newton said. Participants who visited Legal Services New York in mid-October were seeking clarity. Their shutdown anxiety, he said, was “greatly compounded” by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act and its looming cuts to SNAP and Medicaid, new eligibility and work requirements, and the long-term consequences of shifting the costs of the programs to states.

On the one hand, Newton said, it is the combination of different public benefits – SNAP plus WIC, for example – that helps low-income families access adequate nutrition.

“When you’re pregnant or have young children, your need for nutrition increases - so the already inadequate SNAP benefits plus WIC gets you closer to a place where you can provide adequate nutrition and healthy nutrition,” he said.

On the other hand, WIC is “extraordinary” among benefits, Newton explained, because it does not have immigration requirements like SNAP and Medicaid.

“For some families, that is the only benefit they have,” Newton said of WIC. But to get even just that, a pregnant or new parent would have to feel inclined, safe, and comfortable enrolling in the program. For public health experts, the “chilling effect” of the federal government’s immigration-related actions, and the sense of chaos and uncertainty many experience, is a considerable source of concern.

To the alarm of many, days after the shutdown came to an end, the government re-introduced possible changes to the public charge rule, which, if passed, could discourage people from enrolling in public assistance.

Here’s what else to know about WIC.

What is WIC?

“WIC is best thought of as a public health program,” Nell Menefee-Libey, senior public policy manager for the National WIC Association, told Healthbeat in a recent interview. “The goal of WIC is to support and improve pregnancy and birth outcomes, child development outcomes, with a very specific nutritionally tailored food package, with nutrition education, and breastfeeding support.”

Launched as a pilot program in 1972 to address a growing concern over malnutrition and poor health outcomes of mothers and children across the nation, WIC offers eligible families through pregnancy and early childhood direct nutritional assistance (vouchers and cash benefits) and other support.

It is managed at the state level, often through contracted local independent agencies – primarily public hospitals, community health centers, or non-profits. Embedding the program within institutions providing health care services typically helps promote WIC’s mission to improve health outcomes.

WIC’s purchasing guidelines are strict. The benefits can only be used for specific foods, in specific quantities, based on the recipient’s specific circumstances (fully breastfeeding, partially breastfeeding, or not). Covered items include dairy, cereal, canned fish, whole wheat bread, dry or canned legumes, baby food, peanut butter, and fruits and vegetables, through the popular Cash Value Benefits.

Eligibility is determined by income, nutritional risk, and/or enrollment in other public benefit programs, also known as “adjunctive eligibility.” The income limit is set at or below 185% of the U.S. Poverty Income Guidelines. In 2025, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, that represented $59,477.50 a year, for a family of four.

What has been the impact of the WIC program?

Over the past five decades, studies have shown WIC to be effective in improving diet quality (including consumption of important nutrients such as iron, protein, and vitamins); increasing access to early prenatal health care, as well as post-partum and pediatric health care, and reducing adverse maternal and birth outcomes, such as premature births, low and very low birth weight, or fetal and infant mortality.

“The consequences of a child not getting enough nutrition are multifaceted,” Dr. Adam Aponte, pediatrician and CEO of the East Harlem Council for Human Services, said in a recent interview. “It affects brain growth, it affects all sorts of organ systems within the body. If [children] do not have proper nutrition during those early years, that can have consequences for the remainder of their life.”

Aponte highlighted the considerable energy needs for growth of the baby in utero, those of the child in its first two years of life, and the changes to nutritional demands that occur in a pregnant person’s body. WIC, he said, directly helps ensure children and their mothers have access to good quality, nutritious foods and get connected with other forms of support and health care.

For over 40 years, Aponte said, EHCHS ran its own WIC program. Since the organization has a Federally Qualified Health Center component – the Boriken Neighborhood Health Center, which provides pediatric and OB-GYN care – managing a WIC program was “very convenient.” It embodied the embedded, streamlined, and comprehensive continuity of care that makes many WIC programs unique.

But the agency ceased operating its WIC program in 2022, Aponte said, due to a post-Covid provider consolidation effort across the city, and the increase in online and remote services. Other WIC providers serve the area, including the NYC Health + Hospital in Harlem and the Institute for Family Health.

How will cuts to SNAP and Medicaid affect WIC?

The funding deal struck to end the government shutdown includes the full year of appropriations for the USDA, where WIC’s budget resides, Menefee-Libey explained. So its funding is assured through October 2026.

The funding deal gave WIC two other wins, the NWA noted. Reductions to the program’s fruit and vegetable benefits, which had been proposed over the summer in Trump’s and in the House Agriculture Committee’s budgets, were dropped. And the federal government refilled WIC’s emergency contingency fund, which played a key role in holding the program over during the shutdown.

But other cuts to the ecosystem of public benefits are expected this year, and that could affect WIC access.

“Programs like WIC, Medicaid, and SNAP all work together to help to improve public health outcomes,” Menefee-Libey said. “Upheaval or uncertainty in any of these programs doesn’t stay isolated; it will have ripple effects.”

For many of the families Newton’s office helps access, retain, or increase public benefits, losing one, or both, he says, would have “very adverse consequences.”

The consequences are practical: They are about how much food a family will be able to have on the table if they have to manage without SNAP, or what health care will look like for them if they lose Medicaid.

But beside the immediate implications of losing other benefits for a family supported by WIC lies an important bureaucratic “domino effect.”

“If someone is participating in Medicaid and SNAP,” Menefee-Libey explained, “they are presumed to be eligible for WIC – their certification process is streamlined.” That process is called “adjunctive eligibility.” The point of this is to increase the reach of the public benefit programs, and simplify the bureaucratic process.

But the looming changes throw a wrench in the machine. If people lose access to one kind of public benefit, and then become pregnant and want to enroll in WIC, they would, at the very least, need to complete additional administrative steps. But, in the worst case, Menefee-Libey said, they could “lose their eligibility entirely.”

That concern is particularly relevant in the states like New York that expanded Medicaid under the 2014 Affordable Care Act, Menefee-Libey said. The ACA gave states the option to extend Medicaid coverage to address the “coverage gap” that left adults with incomes too high to qualify for traditional Medicaid, but too low to afford for private health insurance – and who often had no access to employment health benefits – with virtually no options.

Now, people who stand to lose access to Medicaid may lose WIC, too.

What would Trump’s proposed ‘public charge’ rule mean for WIC?

On Nov. 19, the federal government reopened the “public charge” rule dossier, as Trump had done in his first term.

The rule refers to a test under federal law that allows immigration officials to deny applications for lawful permanent residence, or a green card, and certain visas if they determine that the applicant could become a “public charge.” The current policy for the test does not consider participation in health care programs like Medicaid, nutrition programs, or housing programs, and focuses instead on cash assistance and long-term institutionalized care. It was established in 2022 and remains in effect.

But the Trump administration is seeking to considerably broaden the test. Effectively, the new proposed rule does not provide explicit guidance as to which benefits would or would not be considered.

WIC providers have said that such an expanded rule could further discourage immigrant and mixed-status families from seeking enrollment in WIC and other benefits.

“The fear is that many immigrant and mixed-status families will withdraw from public benefit programs entirely, including from WIC,” Menefee-Libey said. “We know that will have tremendous implications for public health impact generally – worse health and pregnancy outcomes, and real uncertainty and fear during a challenging period” of pregnancy and early parenting.

Multiple studies have documented the relationship between punitive immigration policies and decreased health care utilization among immigrants (known as the “chilling effect”).

Answering the public comment period for the rule, which is open through Jan. 26, many public health organizations and individuals have voiced opposition. The Protecting Immigrant Families Coalition issued a response, signed by 725 national, state, and local organizations, including PHS, the NWA, New York’s Legal Aid Society, and the Committee for Hispanic Children and Families.

“Unknown rules lead to chaos and bias,” the coalition wrote Dec. 19. “This proposal would remove essential guardrails that protect millions of immigrant families, in favor of an unknown immigration policy that invites arbitrary decisions and political bias. It will deter millions of U.S. citizens in immigrant families, as well as lawfully present immigrants, from seeking care and aid for which they qualify under law. It will undermine the nation’s health and weaken our country’s economy, while making every social problem we face worse.”

Julie Flandreau is a freelance reporter in New York.