This story was originally published by THE CITY. Sign up to get the latest New York City news delivered to you each morning. Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, Anastasiia Tsyunchyk was just finishing medical school. After her studies, she held off from starting a residency in favor of sorting medications and acting as a translator — work, she said, that was more valuable at the time, because as a resident in Ukraine she would not have been able to work directly with patients.

Then, she met Conrad Fischer, a physician at Brookdale Hospital and the residency program director there. Fischer was in Ukraine at the time on a medical mission.

Tsyunchyk applied to the medical residency program at Brookdale, part of the One Brooklyn Health hospital network, and moved here in 2024. At first, she had to make some cultural adjustments. Ukraine, she said, has less of a culture around small talk. But American patients, she found, “want more of an interaction with you.”

“They want to know a little bit more about you, which is a nice thing,” she said.

In Ukraine, patients can much more easily afford essential medicines, Tsyunchyk said. But here, “I’ve had so many people who needed some sort of medications for their heart condition or their kidney condition and it’s going to provide [a] mortality benefit, but they simply cannot afford it.”

At Brookdale, many of her coworkers come from other countries. “A lot [of doctors] are coming from war zones, too, which helped me feel that I belong here,” she said. “Here, I open new horizons for myself.”

But now, her ability to stay and work in the United States may be under threat.

For months, the international medical residents who make up a significant number of the Brookdale physician staff, have been caught up in a whirlwind of restrictions and regulations regarding their visa and travel status.

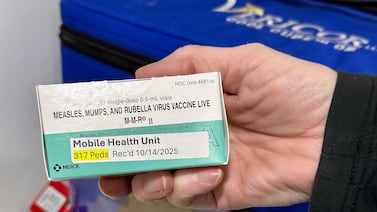

In May, the Trump administration paused interviews for J-1 and J-2 student visas, which many international medical residents work under in the United States. Less than a month later, they resumed. On top of that, travel bans affecting at least 19 countries mean the many international residents of Brookdale find themselves in a kind of limbo.

“We are feeling that we are not valued,” said Tsyunchyk. “We are feeling partially in fear, too, for ourselves.”

“They’re terrified,” Fischer said. “All those people on visas are daily scared that there could be a change in legality.”

NYC hospitals depend on international doctors

The doctors-in-training rely on the hospital for their legal status to be here, and the hospital very much depends on those health workers to operate.

Fischer’s internal medicine department employs 135 international medical graduates, or IMGs, who account for almost all of his doctors. About half of the IMGs are in the United States on visas.

“If we didn’t have international graduates, we would close,” Fischer said. “We could not stay open — because what do you do if you miss 80 to 90% of your doctors? You’re done. We couldn’t go a year.”

According to the National Resident Matching Program, 6,653 positions across the country for first-year residents were “matched” to non-U.S. IMGs this year, out of a total of 37,667 matches. Almost 20% of them — 1,259 — landed in New York state.

New York City’s hospitals have especially high rates of international residents, and most are here on J-1 visas. Those hospitals depend heavily on international residents to staff their departments: surgical wards, emergency rooms, internal medicine, and more.

At Brookdale, the rate of visa-holding residents is even higher, in part because the hospital has challenges attracting American medical graduates.

“Brookdale is a very troubled hospital,” said Bill Hammond, senior fellow for health policy at the Albany-based think tank the Empire Center. The hospital network, and Brookdale in particular, has faced significant concerns around patient safety and finances. Incorporating it into the larger One Brooklyn Health network was “kind of a pet project” of former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Hammond said.

“He was going to turn it around. They were going to become efficient, and it just hasn’t worked out that way,” he said.

Brookdale’s residency program has grown as New York City’s hospitals have been hit by a series of consolidations and closures over the years, and other residency programs have shrunk or closed as a result.

Fischer says he receives 6,000 total applicants for 55 internships, the first year of a three-year residency. Most of those applicants are IMGs, he said.

For Sebastian Arruarana, a residency in the United States offered opportunities to improve healthcare in his native Argentina and globally that he would not have been able to find at home. Arruarana, a third-year internal medicine resident at Brookdale and founder of a network for IMGs, emphasized that international IMGs often fill lower-paying residency positions at hospitals that American doctors are not interested in.

“Not many people wanna work in these underserved communities,” he said. “Sometimes, you end up doing the work of the phlebotomist, the transporter, you’re dealing with a shortage of different things. But it’s part of our practice and training.”

Even local medical students in the city don’t often want to stay in the neighborhoods or boroughs where they study, Fischer said. Medical graduates of the only medical school across Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island, he said, often prefer to work in Manhattan, or other more highly-ranked hospitals around the country.

“Most of those students don’t want to stay in Brooklyn, so you can’t force them to stay in Brooklyn,” Fischer said.

Patients, too, choose to cross boroughs for care, which compounds financial issues for places like Brookdale. Hammond attributed some of its problems to patients electing to go to better-regarded hospitals in Manhattan when they have the choice.

“You go to your local hospital when it’s an emergency, but if it’s not an emergency, and you’re having a baby, or you’re having a hip replacement, or something like that, you go to the hospital with the best reputation, even if that means traveling,” he said. “Brooklyn hospitals in general, and One Brooklyn in particular, is suffering from living in the shadow of all these well-regarded hospitals in Manhattan.”

Visa limbo, travel fears impact doctors and hospitals

When J-1 visa interviews were paused by the Trump administration earlier this year, two incoming residents, from Greece and Pakistan, to Fischer’s internal medicine department were unable to enter the country — one for a few days, the other for a couple of weeks. While they are now settled in Brooklyn, Fischer emphasized that their slots might not have been saved for them at other hospitals.

“They made it, but I want to be clear that other programs, they wouldn’t have waited,” Fisher said. “Most of the program directors would not wait that long, and they would have lost their spots.”

For the international doctors who have made it to the United States, Fischer said many have missed crucial family events — postponing weddings and family visits — for fear of not being able to re-enter the country.

“The J-1 visa program isn’t just so we could do a bunch of nice things for international doctors,” said Fischer. “We drive an 80-hour work week for not even $90,000 for a doctor. And they should not be subject to this treatment where they cannot see their families. Ultimately, that’s not good for patients.”

Arruarana said interviews have resumed for doctors from countries that currently fall under the travel ban. Argentina is not on the list; countries like Haiti, Sudan, and Afghanistan are. To Arruarana’s knowledge, no doctors in banned countries have received visas, despite having waivers that should, in theory, allow them.

“They’re completely left behind, these guys,” said Arruarana. “Those are the ones that are very stressed, the ones that are coming from banned countries — desperate, trying to email congressmen and senators and everyone.”

The impacts of visa and travel restrictions on under-resourced, short-staffed hospitals is just one secondary impact of the Trump administration’s sweeping immigration policies.

“It’s an example of the Trump administration not thinking through all of the ins and outs, not thinking through all the ripple effects of what they’re doing on immigration,” said Hammond. “It doesn’t just affect people who find work in Home Depot parking lots, it doesn’t just affect daycare and home care. It also affects people going to the emergency room at their local hospital.”

Anna Oakes is a summer 2025 reporting fellow with THE CITY and recent graduate of Columbia Journalism School.