This story was originally published by THE CITY. Sign up to get the latest New York City news delivered to you each morning. Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

In a quiet exam room at a clinic in Harlem, the absence of some patients speaks louder than any diagnosis.

For months now, Dr. Chanelle Diaz, a primary care physician with roots in immigrant health, has noticed a troubling pattern: Her undocumented patients — some of whom once relied on safety-net programs like NYC Care and hospital charity care — have stopped showing up.

“I haven’t seen any of my patients on charity care come into the clinic in recent months,” she told THE CITY. “They’ve just gone off the map.”

While it has always been hard to track how undocumented people receive medical care, some new figures and reports from frontline providers show a potentially concerning trend.

This year, for the first time since its creation in 2019, enrollment in NYC Care — a program designed to provide health access to New Yorkers ineligible for insurance, including undocumented residents — has declined.

And while the NYC Health and Hospitals officials who run NYC Care say the dip is due to aging participants transitioning to Medicaid, public health experts warn it may signal something far more troubling: fear of being caught in the Trump administration’s widening deportation dragnet.

Since its launch, the program grew rapidly — from 24,500 enrollees in Fiscal Year 2020 to over 143,000 by 2024, buoyed by community outreach and rising demand.

But according to data obtained from NYCHH, enrollment dropped in the third quarter of FY 2025 to 141,129 members, down from 143,503 at the end of FY 2024.

Though the decline is relatively small, it marks the first downward shift in a program that had been steadily expanding, even amid a historic influx of asylum seekers.

A Health and Hospitals statement said the drop was “largely due to undocumented residents aged 65 and over becoming eligible for Medicaid and thus ending enrollment in NYC Care.”

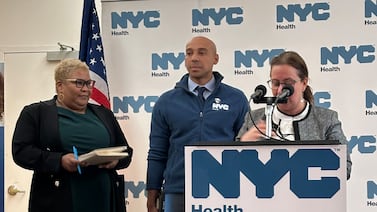

But former city Health Commissioner Dr. Oxiris Barbot isn’t convinced that’s the full story and noted that President Donald Trump’s targeting of immigrants and their rights is also likely to blame.

“I think it’s important to talk about all of the ways the current Trump administration is affecting the health of New Yorkers,” Barbot told THE CITY. “We’ve been concerned about the chilling effect on help-seeking behavior that anti-immigrant rhetoric is having. People are scared.”

Dr. Carolina Miranda, a family physician who has worked in the South Bronx for eight years, said the Trump administration’s ramped up hunt for undocumented people has deepened anxiety among her patients — many of whom are immigrants, asylum seekers, or experiencing homelessness.

“We’ve seen a very significant drop,” said Miranda, who works at a federally qualified health center that partners with homeless shelters and offers mobile medical units to reach vulnerable populations. “In one shelter, which was designated a sanctuary shelter for migrants, the patient volume declined so sharply that we stopped going there because almost no one was showing up for care.”

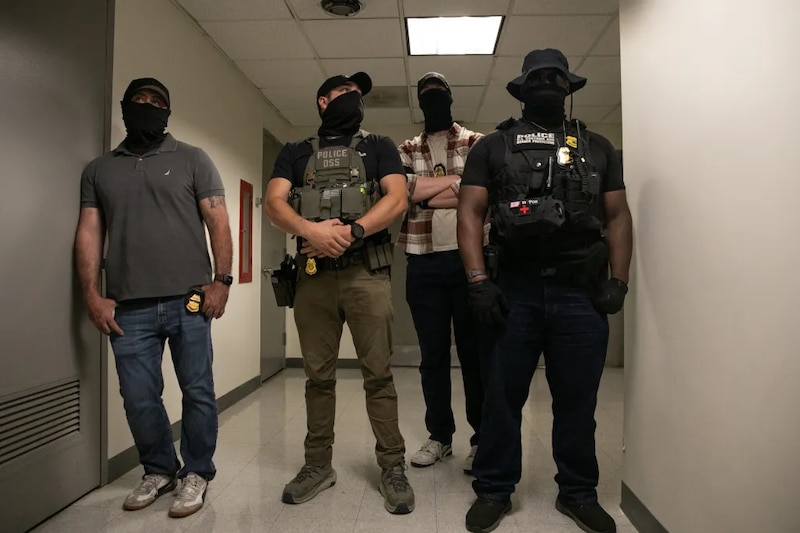

The doctor explained that many patients have stopped seeking care out of fear of Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids or arrests.

“People are afraid to leave their homes. Some tell me they canceled appointments because an app alerted them that ICE was in their neighborhood,” Miranda said. “Others are hesitant to engage with formal medical systems that keep records, worrying it could jeopardize their immigration status.”

Former Mayor Bill de Blasio launched NYC Care as he was ramping up a failed campaign for president. The program guarantees access to care for uninsured New Yorkers — particularly undocumented immigrants who are excluded from Medicaid and other public programs.

City officials stress that the initiative is not insurance: It’s a membership in a network of services provided by NYC Health + Hospitals. Cost is calculated on a sliding scale, with many participants paying little or nothing out-of-pocket.

“Having membership in NYC Care is about connecting people to high-quality primary care,” said Barbot, who currently heads the nonprofit United Hospital Fund. “It’s not sporadic sick care. It’s about prevention, coordinated services, and referrals to specialists when needed. That’s both humane and cost-effective.”

New policies raise privacy concerns

Barbot noted that recent federal policies — such as revelations earlier this year that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services shared personal data with Immigration and Customs Enforcement — could make people wary.

The Associated Press reported in July that CMS agreed to give 79 million enrollees’ information to the Department of Homeland Security, “including home addresses and ethnicities.”

Under the de Blasio administration, City Hall was explicit in its refusal to share immigrant data with federal authorities. The Adams administration says it also does not share information with immigration officials unless the person has been accused of committing a crime.

“We’re not allowed to collaborate for civil enforcement, period,” the mayor said in May.

But Barbot said the mayor needs to do more to make that clear.

“It would be very helpful if the city publicly reinforced that it won’t share data,” Barbot said. “That was certainly the position when the program launched. But now more than ever, people need reassurance.”

The stakes, she added, go beyond individual patients.

“If the funding goes away for how institutions care for undocumented immigrants, it’s only a matter of time before services for other New Yorkers start taking a hit,” Barbot said. “These institutions don’t just serve immigrants — they serve all of us.”

“For those who end up uninsured because of policy changes, NYC Care is one of the only lifelines they have left,” she said.

Hospital officials insist they do not share info with ICE.

“NYC Health + Hospitals does not maintain records or track the immigration status of patients seeking care,” said agency spokesperson Alex Hunter. “We only release patient information with your consent or if authorized or required to do so by law.”

And yet, confusion still abounds, according to Barbot and other medical professionals.

Barbot pointed to broader cuts enacted at the state federal levels — including restrictions to New York’s Essential Plan and looming Medicaid work requirements — as compounding factors. These changes could cause many low-income residents, including immigrants, to lose coverage entirely.

Many people mistake NYC Care for traditional health insurance, they said. Others don’t know it exists. And for some, fear of government surveillance or deportation prevents them from signing up altogether.

“This program needs to be advertised again — aggressively,” Barbot urged. “The city needs to make it crystal clear that NYC Care is safe, private, and here to help.”

Some of that fear has long existed in immigrant communities and predates the Trump election, but Barbot said the current climate has pushed it to a “fever pitch.”

Diaz, the doctor who practices at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and has served nearly a decade as a medical evaluator for people seeking asylum, said the recent federal cuts, combined with escalating fear, are driving this silent exodus.

And for many undocumented New Yorkers, the stakes are life and death.

During Trump’s first term in office, one of her former patients in a former practice, an undocumented man with long-untreated diabetes, ended up in the hospital with a severe foot infection that had spread to the bone while he avoided going to the doctor due to fear of immigration problems.

“He needed an amputation,” Diaz said. “And he was terrified. He’d been in this country working for 40 years. He said, ‘I’ve been paying taxes for 40 years — are you telling me I can’t get any help?’ It was heartbreaking.”

It’s not just new asylum seekers who are avoiding leaving their homes to seek medical care, she added.

“Legal permanent residents, people with visas — they’re all worried,” she said.

The chilling effect of these moves is already being felt, according to Diaz and other doctors focusing on the immigrant community.

“In the past, we could say confidently that your information is confidential, that it wouldn’t be used against you,” Diaz said. “I can’t say that anymore.”

‘Almost no one was showing up for care’

The consequences go beyond a few missed appointments.

“We’re seeing the consequences in real time,” Diaz said. “People end up in the ER with strokes, with complications from diabetes — things that could have been managed with routine care, if they had known where to go, or had felt safe enough to go.”

In the Bronx, Miranda emphasized that the decline predates but worsened significantly after the Trump election.

“This fear is more explicit and severe than before,” she said. “Even when people remain in shelters, they avoid coming downstairs to the clinic because they’re nervous about being documented or stopped.”

Many patients delay specialist appointments they’ve waited months for, and some send their American citizen children to pick up medications to avoid exposure themselves, she added.

The doctor noted that her federally qualified health center does not accept NYC Care insurance, which is mainly used at public city hospitals like Bellevue and Harlem Hospital.

Still, she sees many of the same immigrant populations and noted the overall drop in engagement with city-supported health care programs.

To adapt, Miranda has turned to virtual appointments to reach patients reluctant to leave home, though the shift is limited by patients’ access to technology and comfort with remote care.

She also collaborates with medical-legal partnerships to help patients prepare for contingencies such as possible deportations — including sessions on legal guardianship for children.

“It’s heartbreaking when patients tell me, ‘I skipped my specialist appointment because I was scared ICE was nearby,’” she said. “I try to reassure them, but the anxiety and mental health burden are overwhelming.”

A colleague who specializes in pediatric care has repeatedly been asked if they’d be willing to adopt the patient’s children if they get detained by ICE, according to Miranda.

Some patients are also worried about starting new treatments, she added.

“I have a patient who is a transgender man who is afraid to pursue gender affirming care because he worries about being deported — despite his legal status given his pending asylum case,” she said. “He’s afraid that if he is forced to return to his birth country and has noticeable changes like facial hair and a deeper voice, he will no longer be able to pass as the gender he was assigned at birth, and this would be dangerous for him.”

And the nature of her job has shifted since the Trump election.

“Before, I didn’t have to talk about ‘know your rights’ or deportation fears at every visit. Now, it’s a constant part of the conversation.”

Reuven Blau is a senior reporter for THE CITY.