Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

New HIV diagnoses ticked upward in New York City in 2023, but the estimated number of new infections fell, suggesting possible progress in HIV testing efforts, city health officials said Wednesday.

The number of new HIV diagnoses in New York City has declined significantly over the past two decades, down from more than 5,000 per year in the early 2000s to fewer than 2,000 in recent years. New diagnoses dipped especially low in 2020, likely as a result of pandemic disruptions to healthcare delivery systems.

But new HIV diagnoses have risen in recent years, particularly among Latino New Yorkers. In 2023, 1,686 people in the city were newly diagnosed with HIV, an increase of 7.6% since 2022, according to the HIV surveillance annual report released by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene on Wednesday. At the same time, the city’s estimated number of new HIV infections — which may or not be diagnosed — fell by 17% between 2022 and 2023.

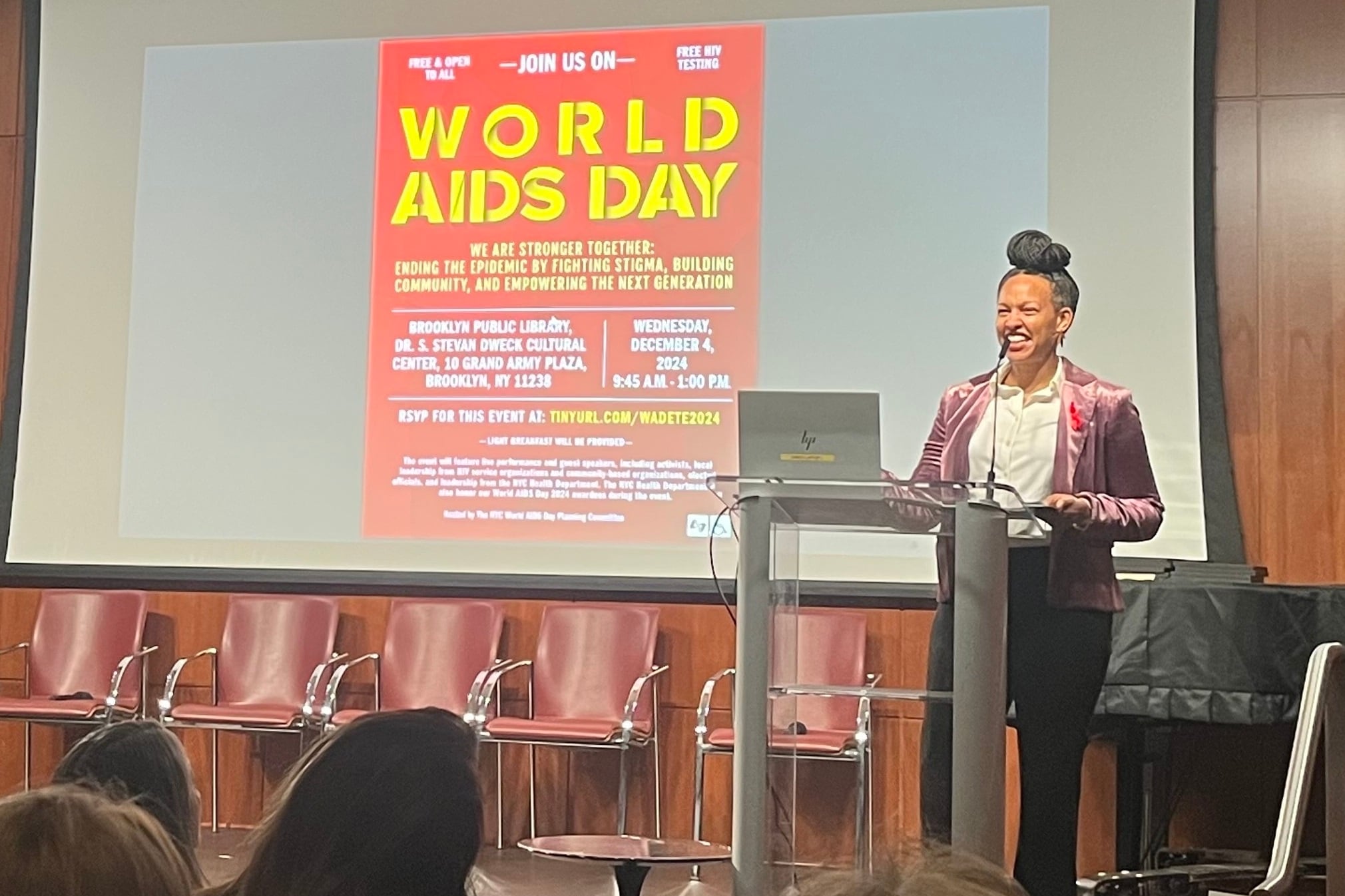

“We have much better infrastructure in place for managing the disease, but we still have work to do,” Dr. Michelle Morse, the Health Department’s acting commissioner, said Wednesday at the main branch of the Brooklyn Public Library during an event commemorating World AIDS Day. “Our health outcomes in New York City remain inequitable across race and wealth, and HIV is no exception, unfortunately.”

Sarah Braunstein, assistant commissioner for the Health Department’s Bureau of Hepatitis, HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections, noted during a presentation that the discrepancy between rising HIV diagnoses and falling estimates of new infections suggests that more existing HIV infections have been diagnosed.

“Our efforts to promote HIV testing, particularly among people who have not accessed HIV services or sexual health care in some time, may be working,” she said.

The Health Department’s report also indicates that racial inequities persist in the city’s HIV epidemic. Black and Latino New Yorkers accounted for 84% of all new HIV diagnoses in 2023. Over the past five years, the difference in the numbers of new HIV diagnoses among Latino and Black New Yorkers has narrowed, and in 2023, Latino New Yorkers surpassed all other racial and ethnic groups for the first time.

From 2019 to 2023, according to city data, people in their 20s and 30s saw the highest numbers of new HIV diagnoses, in comparison to other age groups. Meanwhile, among the five boroughs, Staten Island, Queens, and Brooklyn saw increases in new HIV diagnoses. Additionally, during that five-year period, new HIV diagnoses rose significantly among New Yorkers born outside the United States.

During a panel discussion, public health leaders and community organizers highlighted the hard-won victories in New York City’s fight to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and voiced concerns about how the incoming Donald Trump administration could impact their work.

“We don’t know what the new administration will bring and how that will impact federal resources,” said Ofelia Barrios, senior director of community health initiatives at Iris House, an organization in Harlem that provides support and services for those affected by HIV/AIDS.

The current array of options for the treatment and prevention of HIV/AIDS is unprecedented — and while ending the epidemic is within reach, that victory is far from assured, said Dr. Marcus Sandling, the clinical director of sexual health at Callen-Lorde.

“We are at a cusp of history that could end the HIV epidemic, not only in the United States, but globally,” Sandling said. “And it is literally just a matter of will and political interest in doing that.”

Guillermo Chacón, president of the Latino Commission on AIDS, urged the audience to “fight like hell” to protect global HIV/AIDS health work, including preserving funding for the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

During her remarks, Morse reflected on the value of programs like PEPFAR, which she said she saw firsthand while working in Botswana from 2006 to 2007. During that year, Morse made home visits to HIV-positive residents in an area with a 36-year life expectancy, seeing both the “human cost” of HIV and the sense of possibility afforded by expanded funding for health work.

As public health systems face what could be a “very difficult time” under the Trump administration, Morse emphasized the Health Department’s commitment to working with community-based organizations focused on HIV prevention and treatment.

“We remain committed to protecting and promoting the health and well-being of every New Yorker, no matter what comes next,” she said. “And we are readying ourselves for what’s coming.”

Eliza Fawcett is a reporter covering public health in New York City for Healthbeat. Contact Eliza at efawcett@healthbeat.org .