Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

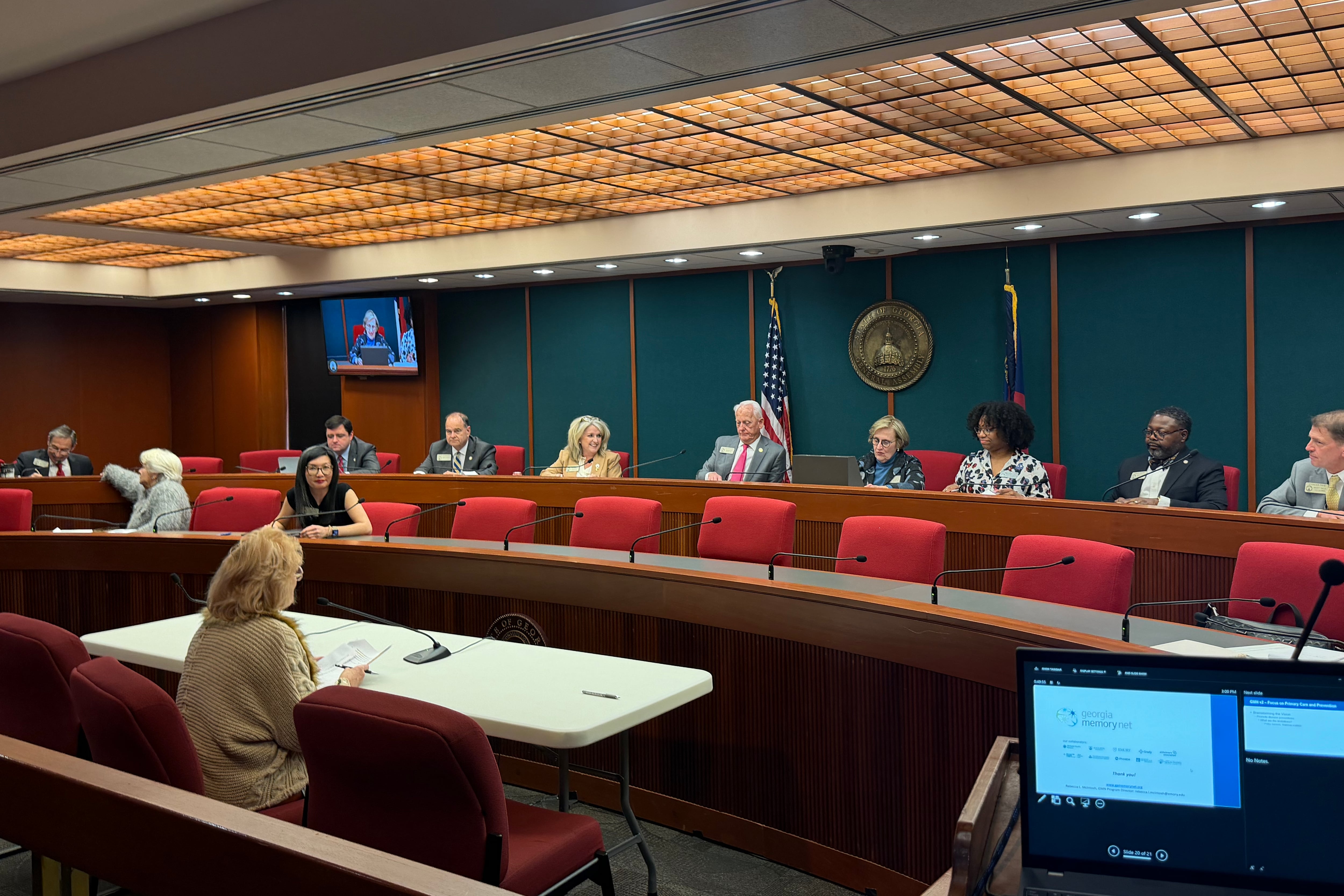

Citing historic underfunding of public health in Georgia, a legislative committee studying how the system is structured and financed has issued five recommendations for change.

In forming the committee, the House resolution noted that less than $1 of every $10 spent on Georgia’s three health agencies goes to the Department of Public Health, which is tasked with disaster and outbreak preparedness and response, air and water quality, disease prevention, and many other areas of population health. (The other two are the Departments of Community Health, the lead agency for Medicaid, and the Department Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities).

The committee’s proposals, developed after hearings around the state with experts and administrators, are aimed at streamlining Georgia’s hybrid public health system, in which control is shared between 159 county health departments and a state public health department. Only one proposal deals with funding, and four of the five would need legislation to enact; one bill has been filed.

“The ultimate answer is that local health departments will – at some point – need more money or will need to cut programs and services. It’s that simple. So it would be nice to see that reflected in here somewhere,” said Scott Thorpe, executive director of the Southern Alliance for Public Health Leadership.

Rep. Darlene Taylor, a Thomasville Republican who chaired the committee, told Healthbeat the legislature will take up increased funding for public health – but not this year. She cited federal budget uncertainty, as well as a need to change the system “piece by piece.”

A House committee has approved the first recommendation to become legislation – a bill to make it easier for county health workers to retain their accrued leave if they move into a state health department job. Taylor said she started there because many public health leaders said it was necessary to create a career ladder for public health workers.

Other recommendations from the study committee could come at the expense of local control, some said.

“These recommendations are sort of contrary. Number one, it says we want counties to contribute more. And then it …. basically says, ‘Oh, by the way, we’re going to do away with any coordination with your local county officials, the people supposed to be raising the taxes for this’,” said Jack Bernard, chairman of the Fayette County Board of Health.

Here’s a look at the five recommendations from the report.

Recommendation: Consider updating the county match requirement for county funding contributions to county health departments.

Rationale: The bulk of local public health funding comes from the state and federal funds.

But counties are also required to contribute funding to local public health departments. The formula to determine how much they contribute is based on population and tax digest data from prior to 1972, the last time the formula was updated, DPH chief financial officer William Bell said during an August hearing.

In fiscal 2024, counties provided a total of $48.5 million for local public health activities, Bell said. That figure is “above and beyond” what counties were required to contribute, which was just $12.2 million across all Georgia counties.

In turn, DPH provided a total of $187.8 million (in FY 2025) to the counties for general public health expenses. That amount is determined through a formula updated each year based on population and poverty levels. DPH also provides counties with additional funds for specific activities like HIV prevention or emergency preparedness.

This is the one recommendation that would not require legislation, said DPH spokesperson Eric Jens. The payments are governed by a contract between each county and the DPH.

Reactions: “Modernizing these public health funding formulas is a really important step toward strengthening our public health infrastructure and being able to keep Georgia’s community safe and healthy,” said Leah Chan, director of health justice at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. But she added that the state should also increase funds for public health.

While some counties might be willing to increase their contributions, in general they are opposed, said Todd Edwards, director of government affairs for ACCG, the association of Georgia’s counties.

That’s because the state House of Representatives is considering a proposal to allow a referendum on whether to significantly reduce homestead property taxes by 2032. If adopted, that would significantly decrease county funding, Edwards said.

“We’re not looking to increase additional expenses on counties when our revenue is about to be decreased,” Edwards said.

The state had a total budget surplus of more than $14.6 billion at the start of this fiscal year, with $5.6 billion in its rainy day fund, officially known as the revenue shortfall reserve, and another $9.1 billion in undesignated reserves.

“The state should have put more money into this and not dump it on the county. Our state is wealthy,” said Bernard, pointing to the surplus.

He said doing so could exacerbate inequalities between rich and poor counties.

“Counties which are wealthy will have no trouble coming up with the matching funds,” Bernard said. But poor counties likely will.

Thorpe said the plan might not work as well as lawmakers expect. Many rural counties have seen their populations shrink since the 1970s, so their contribution would shrink if the formula continues to be based on population.

“The recommendation doesn’t outline a specific funding formula for squaring that circle - but in communities (particularly in South Georgia) that struggle with funding already, there would need to be a clear solution,” Thorpe said.

Recommendation: Allow local board of health staff to retain their accrued leave when they transition to a state appointment.

Rationale: Georgia’s hybrid public health system means that county public health workers are employed by counties, while many district health workers are employed by the state. When local workers move to a state job, they lose their accrued leave rate, akin to taking a step down in seniority.

State and local public health departments together employ nearly 6,000 workers, Jens said.

Reactions: Taylor introduced the bill to enact this proposal, which gained the unanimous approval of the House Public and Community Health committee.

Taylor said the bill aims to create “a sustainable career ladder that will help in improving employee retention in public health.” She said it will ensure experienced county health workers are not disincentivized from shifting to working for the district or state health departments because they would lose their leave rates. That, in turn, could open the door for younger public health workers to join at the county level, she said.

“It’s good for Georgians because it’s allowing them to keep that hard-earned leave as they move to a different position,” Chan said, but more is needed to address the state’s public health workforce shortage.

“We know that recruiting and retaining qualified staff, particularly in rural areas, is a very, very significant challenge. We’ve got below market average salaries. We’ve got a lot of staff that are eligible for retirement in the next five years. So this is really threatening the stability of our public health workforce,” Chan said.

It will be hard for the public health system to compete with private employers and retain staff “without first recognizing and addressing the compensation gap,” said Chris Scoggins, a professor of public health at Middle Georgia State University and a member of the Georgia Rural Health Association board.

Recommendation: Update and streamline the public health system to create clear lines of authority to the state office, consistent service standards, and transparent accountability measures for local health departments across the state.

Rationale: Georgia has a unique public health structure in which each county has its own public health department. Those are then grouped into 18 districts. Each district is headed by a director who reports to the state.

Reactions: Chan said stronger accountability measures for local health departments and districts should be paired with increased funding to ensure they can meet those standards.

Bernard said he’d like to see Georgia require that all public health boards be accredited. Currently only four entities are accredited by the Public Health Accreditation Board: the state DPH; Cobb & Douglas Public Health; Gwinnett, Newton, Rockdale Public Health; and District 4 Public Health, which covers 12 counties southwest of Atlanta. Bernard said the accreditation process helps public health departments plan and then evaluate whether they are meeting their goals.

“The public health certification process takes it away from theory and puts it into practice that you’ve got to set down your goals and objectives, and whether or not you’re achieving the goals and objectives, and what you need to do to modify what you’ve been doing,” Bernard said.

Recommendation: Transition from individual county boards of health to district boards of health, consisting of representation from each county, to consolidate administrative burden on local public health operations.

Rationale: The report states that many rural health departments cannot afford to offer a wide variety of services because of limited resources.

“Rural communities cannot leverage economies of scale as costs increase in rural environments,” the report noted. “The fixed costs of providing public health services within a small county do not scale.”

Reactions: Different states use different models, Thorpe said. Neighboring South Carolina has a highly centralized system directed by the state, he said, while North Carolina public health has a high degree of local control.

The North Carolina model works well because it provides local people and leaders a voice in public health, Thorpe said.

Bernard pointed out another benefit: County boards help mobilize local leaders to work on behalf of public health. Georgia law requires that county boards of health include a member of the county commission, a representative of the school district, a doctor who practices in the county, a consumer representative, and a representative of the largest city in the county.

“The reason you need the local boards is that those are the kind of people on it, and it creates support for public health in those institutions,” Bernard said. He said when his health department was trying to find a new building, members from the county commission and school board helped them find an older county building at a reduced price.

Recommendation: Provide DPH the authority to update health district composition without requiring unanimous local consent.

Rationale: This would allow DPH to shuffle which counties are in each of Georgia’s 18 districts without all of the constituent counties’ agreement. That could make it easier for the state to reconfigure districts to meet current demographics and needs.

Reactions: Bernard said Georgia’s 159 counties make administration unwieldy sometimes. But without further details about how the state would reshuffle the districts it’s hard to know whether to support the proposal.

“To truly modernize our system, greater regionalization will be necessary, without question. Doing so in a way that preserves the voice, values, and lived experience of our rural residents is critical,” Scoggins said. “I am encouraged by the committee’s recommendations, in that, there is a recognition that local input must be preserved yet reimagined.”

Rebecca Grapevine is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Rebecca at rgrapevine@healthbeat.org.