Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s Global Checkup in your inbox a day early.

Hello from Nairobi.

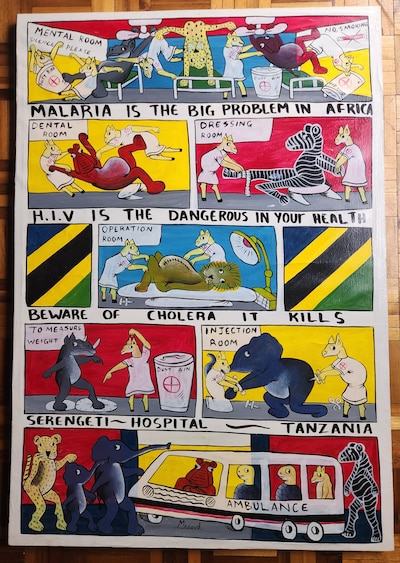

The short seasonal rains have returned, bringing a very welcome, cooling afternoon drizzle. Before we jump in, please enjoy this bizarre and wonderfully thematic painting my spouse just snagged at an U.S. Embassy warehouse auction. (It was sold with a pile of old medical devices, including defibrillators.) We understand it once hung in the embassy medical unit … though I don’t remember seeing it, and we’re puzzling over the Tanzanian flags.

My name is William Herkewitz, and I’m a journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya. This is the Global Health Checkup, where I highlight five of the week’s most important stories on outbreaks, medicine, science, and survival from around the world.

With that, as we say in Swahili: karibu katika habari — welcome to the news.

A shot at ending HIV?

Earlier this year, a new injectable drug to prevent HIV infection called Lenacapavir was approved by both the World Health Organization and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It was hailed as a breakthrough in HIV prevention due to its near-perfect trial results and the fact that it offers protection for six months at a time. The catch? Its maker, Gilead Sciences, set the U.S. price at $28,000 per person per year. That’s 700 times more expensive than PrEP, the widely available, daily oral pill, which costs about $40 annually.

But a newly announced landmark deal all but eliminates the price barrier, the BBC reports. By 2027, Lenacapavir will be manufactured as a generic drug in India, and sold for about $40 per person per year across 120 low- and middle-income countries.

Is the news as good as it seems? I reached out to Mitchel Warren, executive director of the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition. We dove into what Lenacapavir means for the global fight against HIV, and where the gap still lies between having a better drug and actually injecting it into the abdomens of the people who need it.

For the most part, Warren says the celebration is warranted. Taking a pill every day still carries stigma in many communities and relies on daily adherence. A twice-yearly injection clears both barriers, making Lenacapavir a clear winner on the efficacy front. “I hope people come away understanding that this is a huge moment of hope and aspiration,” he says.

Still, the current architecture of the global HIV response depends heavily on the United States, which purchases more than 90% of preventative oral pills through its flagship HIV program, PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Under the Trump administration, PEPFAR has signaled plans to reduce its footprint, narrowing its role to training health workers and procuring drugs and other medical commodities. While this still preserves a potential revenue stream to buy cheaper Lenacapavir, Warren cautions that “procurement is critical, health workers are critical — but they are not sufficient.”

“We have to be very clear that it’s not a miracle drug, and it doesn’t deliver itself,” Warren says. Key to the success of PrEP (which still only reaches 18% of at-risk people) is “demand amongst people who are potentially at risk of HIV, but are not thinking about HIV.”

There are big questions yet to be answered. “We’re talking about delivering an injectable product to people that are otherwise healthy in health systems that are already overburdened. These are not patients, they’re not sick. They don’t want to go to an HIV clinic, so what’s [the approach]? Will pharmacies be able to deliver this? Will community health workers be able to deliver this?” Warren asks.

Still, Warren returns to focus on optimism. “In the midst of lots of hand-wringing and disbelief about what’s happening in the dismantling of the global health architecture, this is an opportunity to lean in and actually do the right thing. It’s a huge opportunity, it’s a huge responsibility, and it’s something that we mustn’t squander.”

Free? Yes. Nutritious? Maybe

Indonesia’s nationwide school lunch program has been rocked by repeated outbreaks of food poisoning, Tempo, one of Indonesia’s leading independent news outlets, reports.

Part of what’s astonishing here is the sheer scale. The country’s “Free Nutritious Meal program” was launched just this year and is a $28 billion initiative that’s planned to feed more than 80 million schoolchildren daily. (That’s roughly equal to the entire population of Germany.)

In the mad rush to scale the program as quickly as possible, the free school lunches have sickened 6,400 children — including 1,000 just last week, the BBC reports. The suspected cause: negligent food preparation, with “cooks to packers to delivery workers” now under investigation.

The context: Yes, this is in many ways a story about Indonesia. But zooming out, malnutrition remains the leading cause of health problems worldwide, and the world is badly off-track on most 2025 United Nations nutrition targets. School meal programs are one of the few solutions with proven, daily impact that can be funded domestically (not just by donors) and reach millions of kids at once. That is … if they don’t get you sick.

More on Ebola’s return to Central Africa

Preface: Last week I shared an Al Jazeera story on how the Democratic Republic of the Congo is facing the first outbreak of Ebola in three years. Dr. Paul Spiegel, director of Johns Hopkins’ Center for Humanitarian Health, told me he isn’t only watching the case and death numbers to see if the containment efforts are a success. He’s also watching whether the response can secure the funding it needs, given the global retreat in emergency health dollars.

How’s the response progressing? Troublingly, according to the Associated Press. It’s still too early to judge how effective the containment effort has been. But the WHO says the outbreak has already “overwhelmed” health facilities in the province at the epicenter of the crisis, with the only treatment center “already at 119% capacity.”

This is partly due to underwhelming fundraising (exactly what Spiegel told us to watch.) Of the “WHO’s projected cost of around $20 million to respond to the outbreak over the next three months,” the international community has pledged less than a fourth — only $4.3 million. It’s worth repeating that previous Ebola outbreaks in Congo benefited from the one-two punch of well-funded responses from the U.S. Agency for International Development and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This time, local officials say the U.S. presence has dwindled to “some small support,” leaving containment efforts at risk unless new donors step in.

And the clock is ticking. Ebola demands enormous resources right at the outset of the outbreak (protective gear, vaccines, basic ambulances, and the footwork of paying thousands to trace contacts in some of the least developed parts of the world). Every delay gives the virus room to spread further out of control.

We’ll keep following this story.

The most ‘least important’ sandfly parasite

The arid northwest corner of Kenya, called Turkana County, has just declared a public health emergency after a surge in the world’s third-most-deadly parasitic disease, The Kenya Times reports.

- Disease breakdown: Kala-azar, also known as visceral leishmaniasis (or, as a bit of a misnomer, as “black fever,”) is a parasite that’s passed by sandfly bites. It causes skin ulcers, fever, and liver damage, and is usually fatal if not treated within two years. It falls into the sad bucket of “neglected tropical diseases,” with no vaccine and very little new medical research devoted to treatments or prevention.

Kala-azar is an illness you’ve probably never heard about. It infects only around 1 million people a year, and unlike malaria, it has no billion-dollar advocacy machine or donor lobby behind it.

Why is this a top-five global health story? (No, it wasn’t just a slow week.) It’s the very smallness that makes it so big. A neglected disease with little outside funding is now testing whether a country like Kenya, which has one of the stronger health systems and economies in sub-Saharan Africa, can mobilize on its own when emergency strikes.

Officials are rushing to respond by detecting cases early, spraying insecticides against sandflies, and outreach with communities. But the backdrop is stark: While working at USAID, I flew into Lomekwi, a small town in Turkana County a year ago (our frightening “runway” was nothing more than a crumbling strip of gravel.) By the end of 2024, USAID was spending more on development programs in Turkana county than the county government itself. Most of that’s gone, which leaves me asking whether a system built on such lopsided outside support was ever sustainable. Or if that largess of development money sowed more harm than good, even before the pullout.

The takeaway: This outbreak is admittedly small, but worth watching. A year ago, foreign donors would likely have stepped in to tamp down the surge in this disease. Now, it’s Kenya’s move, and whether the country can mobilize its own resources for a neglected disease may set an important precedent. I’ll be keeping tabs.

Another pandemic is inevitable

In an Op-Ed in Time magazine, Dr. Seth Berkley warns that the world faces about “a 50% chance [that] another Covid-like magnitude of a pandemic … [hits] in the next 20 to 25 years,” with no guarantee the next one will be any less deadly. (Berkley is a former medical epidemiologist and served for 12 years as CEO of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.)

This is an essay worth reading in its entirety, so let me pull only a few quotes. Berkley makes the simple economic argument for the United States continuing to invest in global pandemic preparedness.

“The billions of dollars the U.S. annually spends on preventing a pandemic is a bargain compared to the tens of trillions it will cost in economic losses and expenses to extinguish a full-blown crisis.”

While he lays out how the current slashing in U.S. global health spending threatens this bargain, he points to a new, dramatic potential cut that I have to admit I wasn’t tracking. “The White House, in its funding request to Congress for Fiscal Year 2026, has called for the elimination of the Global Health Center,” an office in the CDC, Berkley writes.

What does this office do?

“For years, the GHC has had a presence in more than 60 countries (many of them low- and middle-income countries), leading efforts to combat diseases like polio, measles, HIV, tuberculosis, and neglected tropical diseases. It has helped those countries build stronger health systems and train experts to monitor, identify, and respond to disease outbreaks. And it coordinates with many other countries to respond to potential crises before they sweep across the globe.”

Any reason to be hopeful?

“There’s a small bit of good news: Congress is currently showing reluctance to dismantle global health programs. The Senate has already rejected proposed budget cuts, in some cases even increasing funding. The House of Representatives’ stance is mixed, but they are hesitant to approve deep cuts to State Department initiatives like Gavi.”

Thank you for reading. I’ll see you next week.

William Herkewitz is a reporter covering global public health for Healthbeat. He is based in Nairobi. Contact William at wherkewitz@healthbeat.org.