This story was part of Healthbeat’s live storytelling event, “Aha Moments in Public Health,” held Nov. 3 at Manuel’s Tavern in Atlanta. Watch the full show here. Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

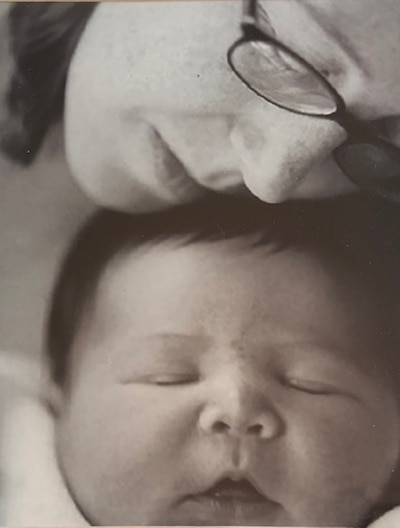

While this story could be named “Why I almost named my son after a hurricane,” instead it tells the story of what inspired me to spend my public health career addressing vulnerabilities in maternal and child health.

On Sept. 16, 2004, two days after delivering my first child, I was discharged from an Atlanta area hospital into the aftermath of Hurricane Ivan. In my post-partum haze, I had no idea what havoc this storm was about to unleash in our lives. At that time, Hurricane Ivan was one of the largest, most devastating hurricanes to hit Georgia, producing tornados, flooding, and power outages throughout the state.

What should have been a 20-minute drive home, took 2 1/2 hours. At one point, we had to pull off the highway so I could feed my son in the car. When we finally arrived at our house, we learned that we had no power and no air conditioning, which even in early fall in Atlanta can create relentless humidity.

This next part may be TMI, but it is important to share that my infant weighed 10 pounds, 14 ounces. Yes, I gave birth to an almost 11-pound baby! What this meant was that he was hungry ALL THE TIME. As the downpour continued, amidst the darkness and heat, we hurried to get settled. For the first hour or so, I tried to breastfeed my new son by candlelight, but through tears, sweat and frustration, I just could not function. I needed my husband’s help to get out of the house and to a hotel, where safety and electricity comforted us through our first night out of the hospital.

This “aha” moment of breastfeeding by candlelight turned into a career inspired to address disparities in maternal and child health.

Unfortunately, being a new mother going through the nightmare of a natural disaster is not a unique or unusual experience, but it is in fact, a dangerous one.

History has shown that pregnant and postpartum women are particularly vulnerable during emergencies. They have functional needs that require additional social and health care-related support, including prenatal and postpartum care and lactation support. Evidence has demonstrated that emergencies can cause heightened stress among this population, often leading to adverse maternal and health outcomes including miscarriage, premature delivery, low birthweight, and mental health challenges.

These were experiences of many women who were pregnant or delivered during several national disasters, including Hurricane Katrina in Louisiana, Hurricane Harvey in Texas, and most recently Hurricane Helene in North Carolina.

There are other types of emergencies that mothers experience that are both harmful and preventable. For instance, extreme heat during pregnancy has been shown to increase women’s risk for severe maternal morbidity and adverse infant health outcomes. The Covid-19 pandemic shed light on the importance of maternal immunization to protect women from complications of infectious disease during and after pregnancy. Even human-caused disasters (such as those caused by bioterrorism) have shown to have long-lasting effects on mothers and their infants.

Through my work, I partner with public health agencies and community organizations to create strategies that improve maternal and child health public health emergency preparedness planning and response. Just recently, I worked with my collaborators from the Morehouse School of Medicine’s Center for Maternal Health Equity and Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Coalition of Georgia to complete Project Prepare, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-funded study of preparedness and readiness for emergency planning among pregnant and postpartum women in Georgia.

Our findings revealed that mothers in Georgia are often disconnected from their health care providers for essential information and support before, during, and after emergencies. They also lack essential financial and social services during emergencies that are needed to ensure healthy outcomes. These findings are important, especially in Georgia, where women experience among the highest rates of maternal mortality.

As both a women’s health advocate and health services researcher, it is my mission to address the vulnerabilities that women experience, particularly during the perinatal period. It is both my purpose and a call to action that I take on willingly and, in these challenging times, with unwavering resolve.

I dedicate this story to my firstborn son, Will – or Ivan as he is fondly sometimes called.

Dr. Sarah Blake, PhD, is an associate professor at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health and serves as director of Emory’s Maternal and Child Health Center of Excellence. A health services researcher, she applies a health equity lens to address women’s health care.