Dr. Jay K. Varma is a special contributor to Healthbeat. Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free national newsletter here.

Many health experts became alarmed last week when they saw the new “About” page on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. The changes to CDC’s mission and priorities, combined with several political personnel appointed to leadership positions, suggest the agency may now be focused more on policy-based evidence than evidence-based policy.

Having worked at CDC for 20 years, I felt dismayed and confused reading about its future direction. On the “About” page, the word “gold” appears seven times, suggesting the agency now seeks a lustrous appearance. “Evidence” is used 13 times, while, at the same time, the text rejects interventions that have substantial evidence favoring them, such as harm reduction in preventing opiate overdoses and housing to improve health outcomes.

The page does not mention the three leading causes of death in the United States (cancer, heart disease, or accidents), nor three of the leading contributors to death (tobacco, nutrition, or physical inactivity). It also explicitly forbids CDC scientists from working on “identifying and documenting worse health outcomes for minority populations.”

In conversations with current and past CDC personnel, I have been debating a question that once seemed unthinkable: Should we tell Americans not to trust the CDC?

RFK Jr. hollows out expert government agency

Many of the people in the current administration view the CDC highly negatively. The recently fired CDC director testified that Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said, “CDC employees [are] killing children and they don’t care.” Why then is the current administration not seeking to eliminate the agency, as it is attempting to do with other agencies that it believes harm America, such as the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Department of Education?

Historians have noted that authoritarian movements often choose to hollow out institutions they do not like and recreate them in their own image, rather than simply abolish them. Doing so preserves the façade of normal governance. The new government can use the brand, language, and structures of respected institutions to give legitimacy to decisions that are inherently political or partisan, rather than fact-based.

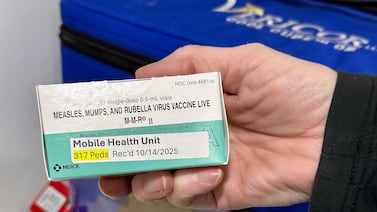

We saw an example of this last week, for example, with CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. ACIP recommendations shape the country’s vaccine schedules, and ACIP members are historically considered some of the nation’s leading experts in vaccines and public health policy.

Earlier this year, however, every member of ACIP was dismissed and replaced with people whose primary qualifications appear to be alignment with the HHS secretary’s vaccine skepticism. The new ACIP chair, Martin Kuldorrf, inadvertently acknowledged this during last week’s meeting, calling his committee members “rookies” in vaccine policy.

This most recent meeting seemed to be an opportunity for vaccine skeptics to air their grievances, rather than a rigorous discussion of benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of various vaccine policies. Public health experts roundly criticized the ACIP members for their lack of scientific rigor, failure to follow established processes, and difficulty clarifying what it was even voting on.

What happened during that meeting is a window into what could happen to the CDC as a whole. The dilemma for outside public health experts is whether to try to preserve public trust in the CDC (and therefore, in the long run, its ability to recover) or to strip away its legitimacy to prevent the public from being misled.

Option 1: Public health experts discredit the CDC as an institution

One approach is the bluntest: Tell the public not to trust CDC at all. This has the advantage of clarity. It signals that the brand no longer means science, and it strips away false legitimacy when the institution is being used to advance decisions, such as with vaccines or sexual health, that directly harm public health. Indeed, this could be considered a moral choice: Deny political leadership the cover of scientific authority.

This approach also has big long-term risks. First, it harms the thousands of devoted civil servants currently working at the CDC and doing essential, high-quality work. Demoralization and attrition of CDC staff are already major problems, and, if this accelerates, the institution will be weakened even more. Second, once the public is told the CDC itself is untrustworthy, the damage may be irreversible. History shows that when faith in institutions is destroyed, authoritarian power thrives. In the Soviet Union, critics who denounced Soviet science often found their words used to justify even more control by party loyalists.

Option 2: Public health experts discredit individual political officials

Another strategy is to focus blame on the political appointees, such as the new CDC director chosen for his political views and the HHS leaders who dictate what can and cannot be said. This allows the scientific legacy of the institution to remain intact while making clear where the problems are. Solidarity within professional communities can be a vital source of resilience in politically difficult times.

But here too there are risks. By personalizing the conflict, critics play into the current narrative that health “elites” are attacking patriotic officials. It risks making the debate about personalities, not about substance.

Option 3: Criticize decisions, defend the rank and file

A third option is more nuanced: Criticize the specific decisions that are tainted, while defending the professionalism of the rank-and-file scientists who continue to produce valuable work. It allows experts to say, for example, that CDC guidance on vaccines is politically corrupted, but that disease surveillance data or outbreak response retain scientific integrity.

This approach has the benefit of preserving hope. It tells the public that science still exists within the institution and that it can be reclaimed. But it requires the public to make fine distinctions in an information ecosystem that rewards simplification, and it may not mobilize people to push back through the media and their elected officials on the damage being done to the CDC.

Is there an alternative source of authority other than the CDC?

My review of history suggests that public health experts should consider a balance between options 2 and 3. Name the political appointees and the processes by which scientific judgment is being censored. Defend the professionalism of CDC scientists and affirm the real science that still exists. Criticize decisions that are dictated primarily by politics. Make clear that this is not just about science but about democracy itself. Citizens have the right to institutions that serve them, not a party line.

For this strategy to work, it must be coupled with an alternative source of authority. We already see this happening, for example, with professional societies, academic institutions, and state coalitions issuing their own vaccine recommendations. I suspect we may need similar entities to verify official pronouncements and to highlight omissions or distortions for HIV, sexually transmitted infections, vulnerable populations, climate risks, and other contentious issues.

Those of us who devoted our careers to the CDC know how painful it is to even consider these strategies. But the public deserves institutions that speak first and foremost for science. Until the CDC is restored, experts have a duty to protect and fill that gap.

Dr. Jay K. Varma is a physician and epidemiologist. An expert in the prevention and control of infectious diseases, he has led epidemic responses, developed global and national policies, and implemented large-scale programs that saved hundreds of thousands of lives in Asia, Africa, and the United States.