This is a guest essay for Healthbeat. Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free national newsletter here.

Public health experts agree that five interventions saved the most lives in the past century: clean water, sanitation, nutrition, vaccines, and antibiotics. Will artificial intelligence join that list in the 21st century, helping to avert illness and extend life expectancy?

Having led public health programs around the world for the past two decades, I believe that AI represents the single biggest opportunity to improve public health in my lifetime. As new diseases emerge more rapidly, and climate change increases other threats to health, officials may be able to use AI to practice public health with greater speed, precision, and effectiveness.

AI revolution in health amplifies intelligence

In his 2024 book “The Coming Wave,” Mustafa Suleyman describes how humans came to dominate the Earth through their intelligence — the ability to develop, transmit, and implement ideas — and the application of that intelligence to develop energy, cultivate food, improve shelter, and enhance health. AI is, of course, the culmination of that process. We have created technology that amplifies our intelligence far beyond our biological capacity, allowing us to build things we never could have built before.

Generative AI tools like ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and Microsoft Co-Pilot have demonstrated how AI dramatically improves the speed and productivity of “cognitive labor,” particularly writing text for humans, code for computers, or analyses of data in written or numeric format. This is why some also prefer to call it “augmented intelligence.”

The next waves of AI will go beyond ingesting and producing text to augment other functions of the human brain, such as vision, hearing, and speech.

How will AI improve health care delivery and R&D?

Billions of dollars are being invested around the world to design and implement AI for health-related purposes. The health sector can broadly be classified into three areas: research and development; health care delivery; and public health. Much of the money is flowing into the first two areas of the health sector.

Investments in health research are particularly promising, because practical uses of AI are emerging at the exact same time as another transformative technology is also emerging: synthetic biology.

Decades of research into biology has given scientists tools to decode the genes behind all forms of life and, most important, write that genetic code to create new biological entities that treat disease, kill pathogens, break down waste, and make new materials. Developing new products for human health — drugs, diagnostics, vaccines, and devices — requires years of intensive work across multiple disciplines. In drug development, this includes optimizing the formulation, dosing, and delivery in animals and then humans, and, most important, to demonstrating safety and efficacy in large, diverse populations using rigorous protocols. Much of this work is repetitive, cognitive, and rule-based, the kind of pattern-heavy work AI is built to do.

Especially in the United States, where health care accounts for over 20% of the economy, there is tremendous investment into AI to improve how health care services are delivered to individual patients. Entire medical journals, and sections of prestigious medical journals, are now devoted to the burgeoning field of digital health. AI has already moved from the developer’s screen to the clinic with chatbots, scheduling, decision support, diagnostic support, and care management. At my clinic, we are testing “ambient AI” technology in which a system listens in the background while I perform a history and physical examination on a patient, then serves as a digital, autonomous medical scribe, preparing notes and orders for me to review and approve.

Many believe that it is not long in the future until the first interaction a person has with a doctor is an AI physician. Multiple studies have shown that AI can already out-perform clinicians on screening, diagnosis, and treatment in different clinical settings and patient populations.

Public health practice needs AI investment

Where does that leave public health, the third part of the health sector?

In its most broad sense, public health means everything a society does to prevent disease and promote the health of humans. Public health practice refers to the work of people in public health, including: monitoring the health of a population, developing and implementing policies and programs to improve health, generating evidence to guide health policies, and responding to outbreaks and other emergencies. Most of this work is done by people working for government, because most countries recognize that public health is a form of public safety, like police and defense, and that private markets alone cannot meet its demands.

With sufficient resources and political will, current generative AI tools could be used right now to improve:

- Ingesting, cleaning, and analyzing surveillance and other health-related data, including nowcasting and forecasting for different scenarios

- Aggregating evidence and local data from diverse real-world sources to aid decision-making during routine health operations and emergencies

- Tailoring reports, written communications, and graphical media to different audiences, including elected officials, media, and general public

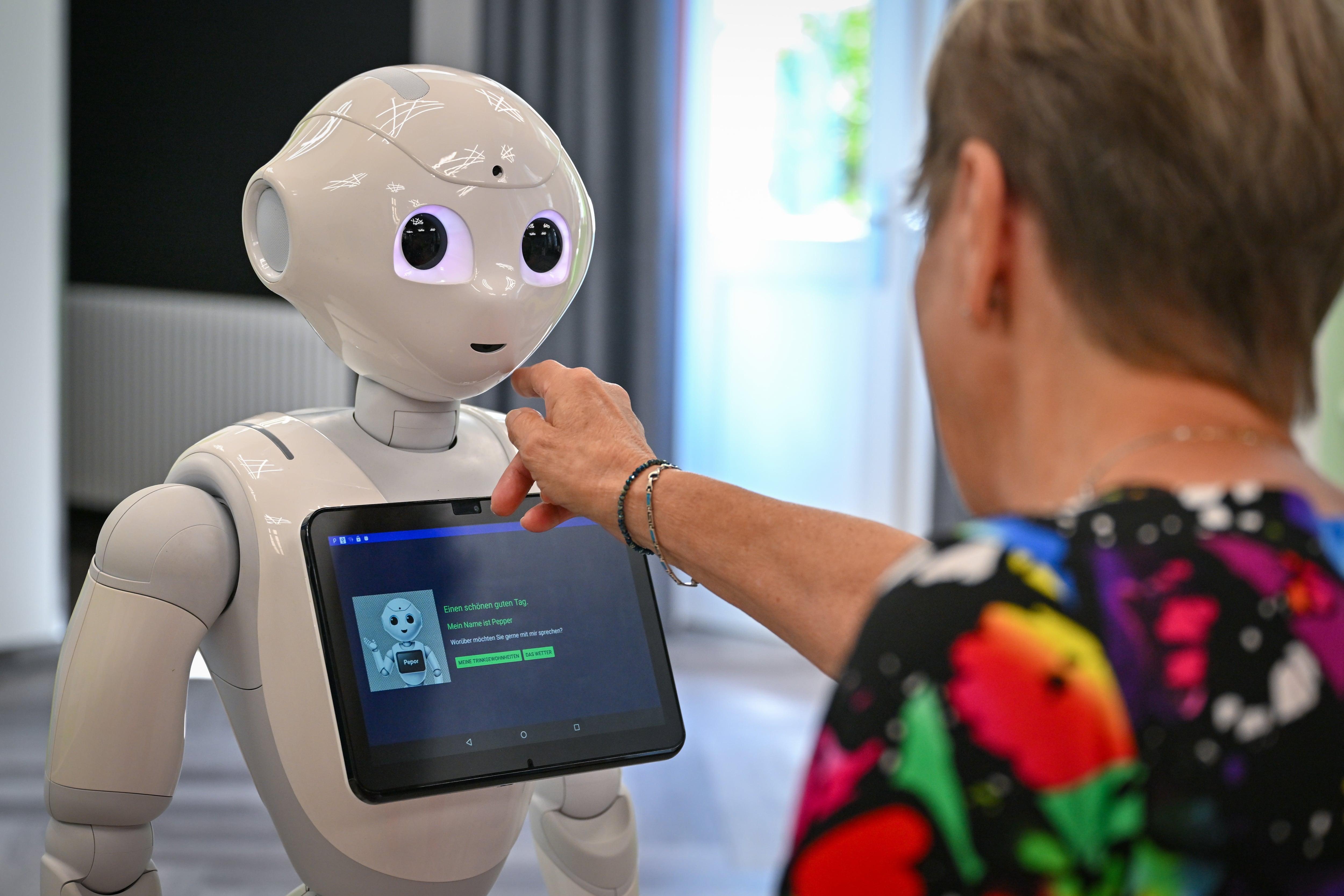

- Improving health care service delivery for immunizations, sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and maternal child health programs through chatbots, medical decision support, and patient engagement before and after services

- Preparing applications and reports for grants and other outside funders

Four critical challenges for public health and AI

While I am optimistic about the future of AI for improving health, I do worry that public health practice could still fall behind or, worse, be harmed by AI. Here are my top four concerns.

The public health workforce

Much of the work in public health agencies can broadly be considered cognitive manual labor. I previously hoped that AI could be used for task shifting. For example, a public health program that currently requires 10 epidemiologists could use AI to shift at least half of them away from desks to working directly with communities on disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and emergency response — a shift that could address one of the ways public health struggled during COVID-19.

In 2025, however, there have been widespread efforts to dismantle public health domestically and globally, with agencies gutted, funding slashed, and legal authorities reduced at the state and federal level. The Department of Government Efficiency initiative includes efforts to fire federal workers and replace them with AI, rather than shift those workers to other services. Will a new public health agency that relies on AI be able to maintain essential public health services? What happens in an emergency when public health workers who would normally be reassigned from routine work to emergency response are no longer available?

The investment gap in public health

AI investment chases profit, which means AI funding will inevitably flow to financial markets, business and consumer applications, and entertainment. For the health sector, AI funding will flow to the areas where there is the most money to be made: developing new drugs and caring for sick people.

The private sector rarely invests in technology to support public health practice. As chronically underfunded government entities, public health agencies cannot pay the same rates for software and equipment that the private sector can, and the tools that public health agencies need are often highly specialized and have limited utility for business or other private sector customers.

The best hope then is that AI applications developed for other sectors — health care delivery, biotechnology, defense, academia, public relations — can be adapted for public health. That is, public health becomes a secondary adopter of AI, rather than the primary developer or customer. Will AI technologies for research, health care delivery, and other sectors meet the needs of public health agencies? Will the cost of adapting them be affordable, and will there be sufficient interest from companies to invest in adapting them for public health uses? Will tools like generative AI chatbots evolve enough to improve public health practice?

Leadership and innovation

Public health agencies tend to lag behind other sectors on adopting new technologies. They operate under a scarcity mindset and worry, appropriately, that their budgets will be cut if they try to innovate and that innovation fails. Because they are entrusted with highly sensitive personal data — identifying information about a patient and their diagnosis of syphilis, HIV, or other disease — they also hesitate to adopt any technology that might risk exposing a patient’s identity to the public. Where will agencies find the bold leadership to design and develop AI systems amid these longstanding challenges and a future landscape of less authority, staffing, funding, and credibility?

Ethical implementation

AI ethical risks include data privacy, bias, and inequality. AI systems gather and analyze large amounts of data, potentially allowing the confidential health history of a patient to be accessible to staff who should not have access in the first place and, far worse, to expose that data to the public through an inadvertent data breach. AI systems are also trained on data collected by humans, so are embedded with the same biases of individuals and human-created systems. Similarly, the benefit of AI is likely to be highly asymmetric, with well-resourced countries and localities reaping an exponential benefit and exacerbating health inequalities. What protections will be built in to protect privacy and ensure the ethical application and distribution of AI for public health? Who will be held accountable if they fail?

More debate needed about AI in public health

It is abundantly clear that AI is a general use technology — like the printing press or electricity — that will completely transform society, but I have been surprised at how little public discourse there has been about how AI can be applied now to improve public health practice and disease control. We need more open discussion and debate about how AI can strengthen, and not replace, public health workers.

Dr. Jay K. Varma is a physician and epidemiologist. An expert in the prevention and control of infectious diseases, he has led epidemic responses, developed global and national policies, and implemented large-scale programs that saved hundreds of thousands of lives in Asia, Africa, and the United States.