This is a guest essay for Healthbeat. Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free national newsletter here.

When Americans think of public health, they likely picture people giving vaccines or speaking at press conferences during a crisis. They probably do not picture the public health laboratories that serve as essential infrastructure for monitoring and responding to infectious diseases, environmental hazards, chronic diseases, and maternal-child health.

In recent months, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services eliminated two specialty laboratories operated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and withdrew funding that had been awarded under the previous administration to enhance state and local public health laboratories. These changes have received little attention, even though they hinder the country’s ability to monitor and respond to a wide range of public health threats.

What are public health laboratories?

Every state has at least one public health laboratory, and a few large cities — such as New York City, where I helped oversee operations from 2011 to 2017 — run their own. Funded by local, state, and federal budgets, public health labs perform tests that serve the public interest and may be too expensive, rare, or complex for commercial or academic facilities. They are staffed by microbiologists, molecular biologists, chemists, and other technicians who often have specialized training and equipment that is not widely available elsewhere. Here are some of the more notable functions performed by these labs.

Public health labs confirm diagnoses when private labs cannot

One of the most important roles of public health laboratories is performing high complexity tests for rare diseases that most hospital and commercial laboratories do not.

For example, during my time overseeing infectious diseases for New York City, I had to order microbiologists to come in after hours several times a year to test an animal for rabies after a person had been bitten. Few laboratories accept as a specimen – at any time of day or night – “refrigerated head of suspected animal only. Bats (killed) may be submitted as whole carcass.” But public health laboratories do.

Another example is testing for botulism, a rare, lethal cause of full-body paralysis that usually results from food that has been improperly prepared and stored. Confirming the diagnosis is essential for patient care, because it is treated with a special anti-toxin, and for the public’s safety, because if one person has botulism, it is likely that others were exposed as well. Public health labs confirm botulism by injecting mice with a patient’s sample and observing for signs of paralysis or death, indicating the presence of botulinum toxin.

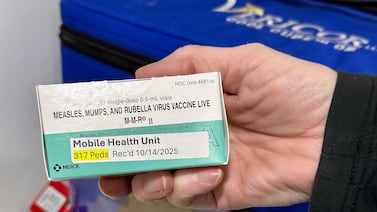

When new diseases emerge in the United States, the CDC relies on a network of laboratories, known as the Laboratory Response Network, to develop, validate, and deploy new laboratory tests. The network includes public health laboratories that can rapidly implement new tests on dangerous pathogens. These laboratories also help evaluate how easy they are to perform and how accurate they are before the CDC and private companies turn these tests into kits to be used by laboratories that lack specialized staff training and equipment.

During my time in New York City, our public health laboratory performed the first tests for Ebola and Zika viruses before academic and commercial labs could do this testing. During Covid-19, this phased deployment from the CDC to public health laboratories also played a critical role in identifying problems with the CDC’s initial SARS-CoV-2 assay.

When there is a suspected case of bioterrorism, specimens must be handled with a special chain of custody, because they are part of a criminal or national security investigation. In those situations, government-operated laboratories are essential, because staff have the necessary training and security clearances. A frequent example is “white powder” incidents, in which a person opens an envelope with a threatening message and white powder, recalling the anthrax bioterrorism attacks in 2001.

Testing at scale to contain outbreaks and conduct surveillance

Even when tests can be performed routinely in another laboratory, public health labs may be the only facilities willing to perform testing.

When there are outbreaks at a food service establishment, such as hepatitis A or Salmonella, public health agencies may need to test a large number of employees and patrons. In such situations, public health labs are the only ones that can handle a sudden surge in specimens. They may also be the only ones able to cover the cost of testing, because individuals would not want to pay, and commercial insurance companies would likely deny reimbursement for tests that primarily serve the public interest and likely do not change individual clinical care.

Similarly, when public health agencies need to monitor the incidence of routine diseases, they need to collect and test specimens from patients, even if those patients would not normally require testing for medical care. For example, public health laboratories play an important role in monitoring seasonal respiratory viruses, systematically testing patient specimens for influenza, RSV, and other pathogens for “virologic surveillance.”

Public health laboratories also perform additional testing of pathogens to answer important public health questions. This type of testing — known as sub-typing — includes: susceptibility testing to monitor drug-resistant infections; PCR testing for rare strains of a virus (e.g., H5N1 testing on non-typable influenza A strains); or whole genome sequencing to investigate whether multiple people were infected from the same source (e.g., Listeria) and to monitor for new variants of viruses (e.g., Covid-19).

Specialized labs test for non-infectious threats to health

Public health agencies have responsibilities beyond infectious diseases that require support of a specialized laboratory. Labs may do routine or reference testing for water, air, soil, and consumer products to test for chemical or other contaminants that can endanger health.

All states require newborn babies to be screened for conditions that, if detected before symptoms appear, can be treated to prevent severe disability, intellectual impairment, and death. Examples include phenylketonuria, hypothyroidism, cystic fibrosis, and severe combined immune deficiency. Most states rely on public health labs to perform this testing, ensuring they are performed quickly and accurately using standardized protocols.

Can these tests be shifted to commercial or academic labs?

Some might wonder: Why can’t commercial or academic labs take over these functions? Public health labs address a market failure. Testing for rare, emerging, or environmentally related diseases is often unprofitable. Commercial labs are unlikely to invest in these tests, and academic labs often lack the infrastructure for high-volume, round-the-clock operations and partnerships with law enforcement. Moreover, academic labs often have not undergone the rigorous inspection and certification process needed for results that alter patient care.

The impact of budget cuts

The cuts to CDC and state laboratories are likely to result in delayed or missed disease detection, longer turnaround times for results, and fewer personnel to handle crises. Although public health laboratories often operate in the background, the impact of cuts will be felt directly when people are unable to get results quickly after they have been bitten by a raccoon, experience delays in treatment for a baby’s metabolic disorder, and have less data to understand illness in their community.

These labs have long been under strain. Many struggled during the Covid-19 pandemic to keep up with surging demand and shifting federal guidance. Cutting public health labs may seem cost-saving now, but it’s likely to prove more expensive over time when considering preventable illnesses, delayed outbreak response, and lives lost.

Dr. Jay K. Varma is a physician and epidemiologist. An expert in the prevention and control of infectious diseases, he has led epidemic responses, developed global and national policies, and implemented large-scale programs that saved hundreds of thousands of lives in Asia, Africa, and the United States.