Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

Meals in public schools and city-run hospitals are set to become healthier, as New York City rolls out new food standards that ban processed meats, restrict artificial colors, and promote whole foods.

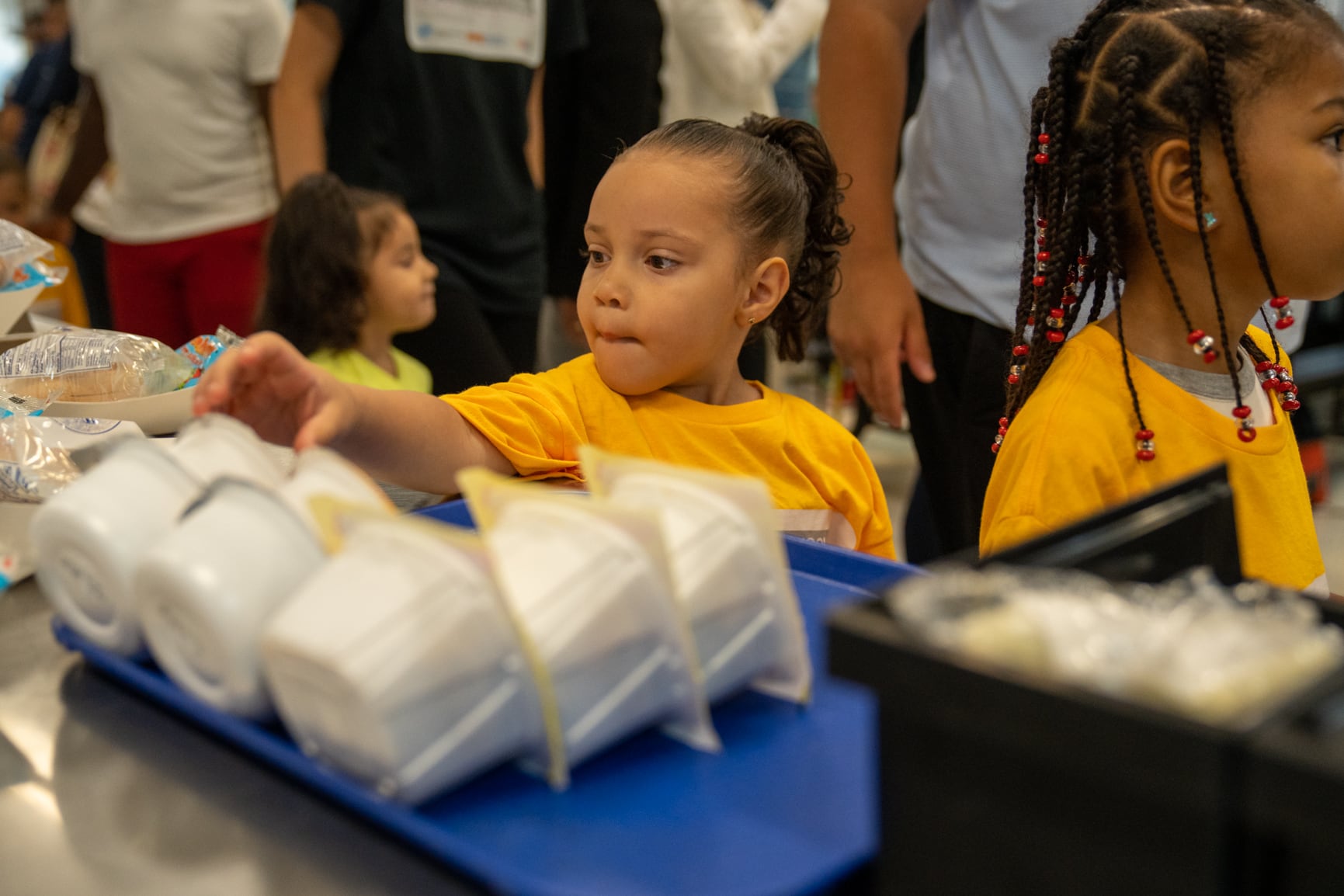

The new standards, which take effect on July 1, will impact about 219 million meals and snacks served annually by 11 city agencies, from school lunches and hospital meals to home-delivered meals for elderly New Yorkers.

“I often say, when it comes to your health, it’s not just what is in your DNA, it’s also what is in your dinner,” Mayor Eric Adams said in a statement. “I’ve turned my life around from being pre-diabetic to living a plant-based diet, and when we came into office, we committed to ensuring all New Yorkers have access to healthy, fresh foods.”

New York City will tighten restrictions on artificial colors, low-calorie sweeteners, and certain additives and preservatives. Processed meats will be banned, with a recommendation against food products that are pre-prepared by deep-frying, including chicken nuggets, mozzarella sticks, and potato tots. Under the updated standards, the city will recommend whole or minimally processed food, meals cooked from scratch, and locally sourced ingredients whenever possible.

First established in 2008, the city’s food standards are required to be revised every few years. The new standards build on the city’s existing restrictions on artificial ingredients and processed meats. They also reflect a citywide effort to combat chronic and diet-related diseases, which are leading causes of death for all New Yorkers and disproportionately impact Black residents.

Dr. Jennifer Cadenhead, an assistant professor at the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy, described the new food standards as “very thoughtful” and said that they would positively impact families who rely on city-distributed meals. The expanded restrictions on sweeteners, artificial colors, additives, and preservatives were especially important, she said.

“The things that they’re prohibiting have either not been well studied in humans, or there has been some indication that they could cause illness in humans,” she said. “So why would we feed our children food that we’re not really certain about?”

Cadenhead noted that the more that children are exposed to healthier options when they are young, the more likely they are to accept those foods when they are older. Reducing exposure to unhealthy foods can help “delay, or maybe prevent, other illnesses or adverse health conditions,” she said.

As part of HealthyNYC, the Health Department’s campaign to increase New Yorkers’ life expectancy, the city aims to decrease heart- and diabetes-related deaths by 5%, and screenable cancer deaths by 20%, by 2030. Poor nutrition, tobacco consumption, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol use are the key drivers of most chronic diseases, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acting Health Commissioner Dr. Michelle Morse said in a statement that the new standards “underline our longstanding work to ensure New Yorkers have access to healthier foods while advancing our commitment to health equity and climate health.”

On the federal level, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has emphasized the link between poor diet and chronic disease and has made the elimination of food dyes and other additives a top priority. And while the city’s new food standards may reflect a point of alignment with the federal government, experts caution that the Trump administration’s cuts to programs like SNAP and Medicaid are poised to significantly harm New Yorkers’ health.

“These standards are really important,” said Dr. Nevin Cohen, an associate professor at the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy and director of the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute, whose team discussed the standards with city agencies while they were in development. “But to improve population health also requires support for households through programs like SNAP and WIC and access to medical care through programs like Medicaid.”

He added that if the scale of cuts to those programs is as extensive as expected, “these changes at the local level in food standards will be outweighed by the negative impacts of these larger national policy changes.”

Eliza Fawcett is a reporter covering public health in New York City for Healthbeat. Contact Eliza at efawcett@healthbeat.org.