Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

Growing up as the daughter of immigrants from El Salvador, Roxana Chicas heard horror stories about what the heat could do to construction workers like her stepfather.

Stories of a worker who got dizzy and fell off a roof, a farmworker who fainted in the field and was run over by a tractor trailer, and the daily challenges of working outdoors under a “blazing sun” inspired Chicas to devote her career to researching the impacts of heat on the body.

“I remember those stories and carry them with me in everything that I do now,” said Chicas, an assistant professor of nursing at Emory University in Atlanta. She and a team of researchers from Georgia Tech have developed a new device to help outdoor workers monitor how heat is affecting their bodies and collect data to better understand the effects.

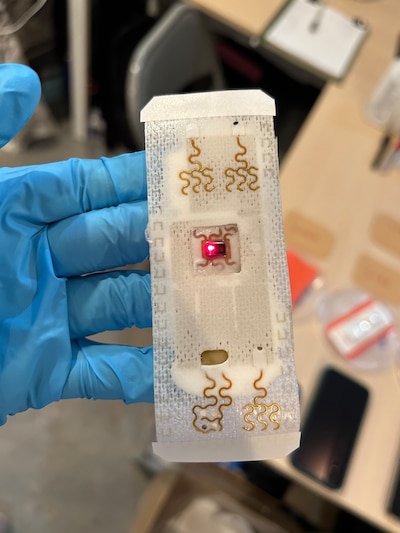

People who do intense physical labor in high temperatures and become dehydrated are at risk of kidney damage. The new device, a two-inch patch worn on the chest, measures those indicators and alerts wearers to take a break and rehydrate. The sensor, which connects to the wearer’s phone via Bluetooth, tracks physical activity, oxygenation rate, respiration rate, heart rate, and skin temperature.

The project, funded by a five-year, $2.46 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, developed from Chicas’ research with farmworker groups in Florida.

“Many farmworkers work in rural communities. They are often unseen, but they are often at the front lines of climate change,” Chicas said. “Oftentimes workers will push themselves to continue working … they just feel like they have to power through.”

But that could seriously damage their bodies or lead to heatstroke, she said. Chicas and other scientists have identified associations among outdoor work, dehydration, and physically intense labor and acute kidney injury, although they don’t fully understand the physiological mechanisms behind that. Repeated multiple times, acute kidney injury can cause chronic kidney injury, she said.

Heat is a public health problem, with farmworkers 35 times more likely than others to die from heat-related causes, according to a 2016 study in the American Journal of Industrial Medicine. A 2018 study in Lancet Planet Health found that 15% of people who worked under heat stress experienced kidney disease or acute kidney injury.

Earlier this year, the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health and 86 other organizations sent a letter to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration urging it to finalize heat protections for workers.

Besides kidney damage, heat can cause respiratory problems, and it’s been associated with higher rates of preterm births and low birthweight.

The idea for the sensor came from Chicas’ community-based research with a mostly Spanish-speaking farmworker population in Florida and Georgia. Georgia had about 44,000 farmworkers in 2022, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Census of Agriculture.

Chicas and her team asked the workers to name their top concern, expecting the answer to be pesticides. The workers said it was heat.

“They started talking about how hot it is, how they feel like it gets hotter every year … They just don’t know how to consider exactly what’s happening, but they feel different,” Chicas said.

That response launched her team down a path of multiple smaller studies to better understand what was going on. One study found farmworkers’ core body temperatures after work reached 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees Fahrenheit) and higher, which significantly increases the risk of heatstroke, Chicas said.

They found that a cooling bandana around the neck can provide better relief than a cooling vest, and that workers who drank 5 liters of water with electrolytes did not get dehydrated, while workers who drank the same amount of plain water did.

Chicas said the heat sensor project will use machine learning to mine and analyze data from the sensors. Most workers have smartphones, she said, and are eager to try new things.

Community groups that work with farm laborers in Florida recruited a group of 18 volunteers to try out the sensor in July 2021. In exchange, the study organizers provided the workers with detailed health data, including cholesterol, blood sugar, kidney function, and other indicators.

“They have said to us that that’s the number one reason why they participate, because they want to know about their health, because many of them do not have access to health care,” Chicas said.

Cristian Estrada, South Georgia organizer for the Latino Community Fund of Georgia, said the farmworkers he works with aren’t guaranteed breaks. Their working hours have shifted earlier and earlier, so they can finish before the heat of midday, which can reach an average of 95 degrees in July, according to the National Weather Service.

Estrada said he likes the idea of a sensor to help workers and highlight the problems faced by farmworkers.

“It’s a great way to just find out more about a community that’s underlooked,” Estrada said.

Chicas and her team want to see the product on the market – at an affordable price – within the next year or two.

“This is a population that really is the backbone of the food industry and really requires some attention from us to help them stay healthy so that they can continue being the backbone of the food industry,” Chicas said.

She said she wants to see greater federal and state protections for outdoor workers.

“We’ve all agreed we don’t want people dying in the fields,” she said.

Rebecca Grapevine is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Rebecca at rgrapevine@healthbeat.org.