Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free Atlanta newsletter here.

Latinos, who make up at least 11% of the state’s population, face serious barriers to health care, especially mental health services, according to the State of the Latino Community in Georgia report released Tuesday.

“Immigration is a social determinant of health,” according to the report, which cited immigration status, transportation, and language among the challenges in gaining access to care.

In 2022, 58% of the about 1 million Latinos in Georgia were born in the United States, and that share is increasing.

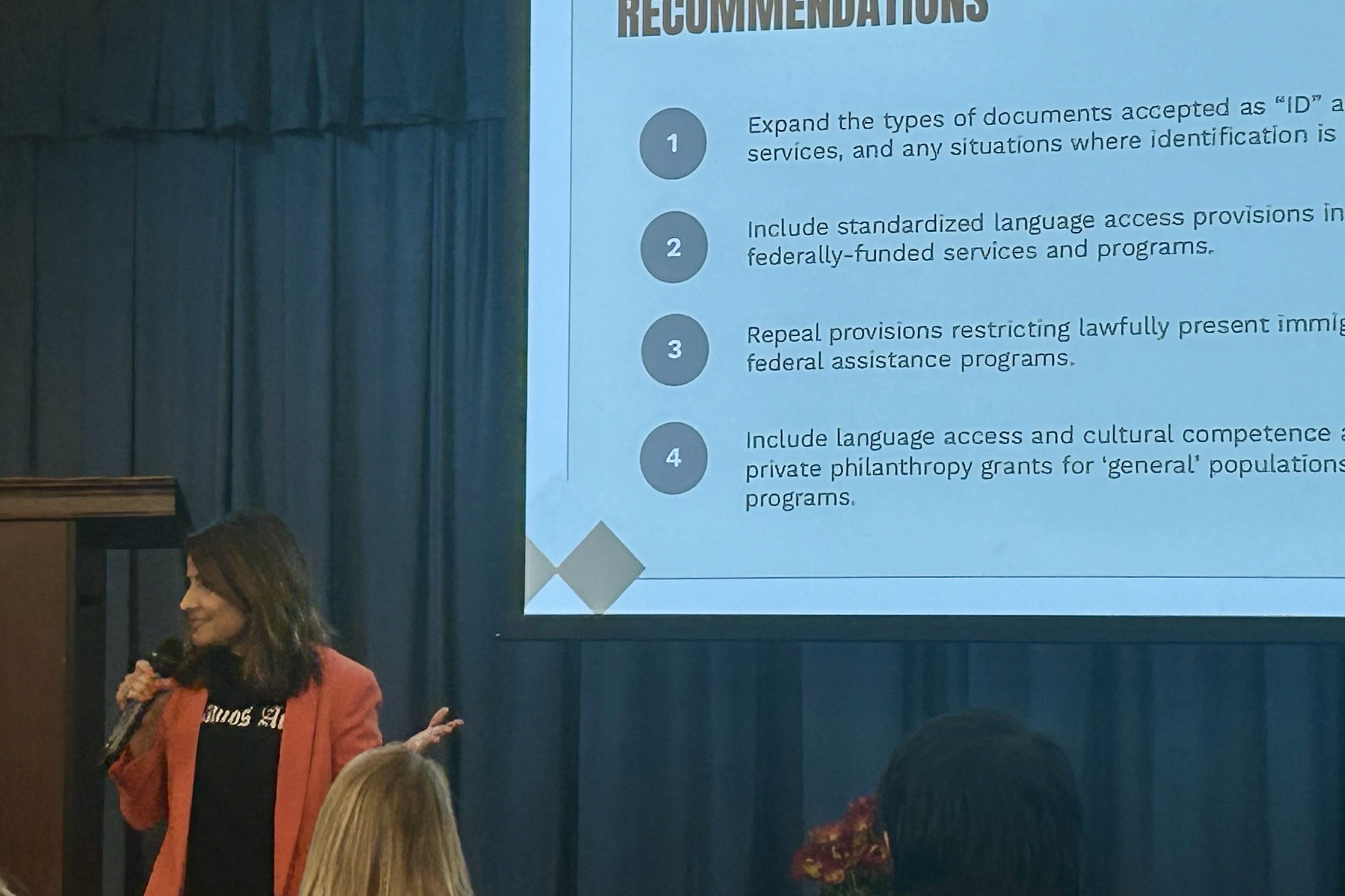

Community leaders discussed the report at the 10th annual Latino Summit in Norcross. The report was sponsored by a group of community organizations led by the Latino Community Foundation of Georgia and Ser Familia, a nonprofit organization that provides social services.

The report combines quantitative data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Georgia Department of Public Health with individual stories and insights from Latinos in the state. Data in the report is limited with a lack of statistics disaggregated by race and the difficulty of counting undocumented immigrants.

The report covers a host of issues, from economic development to the arts. Here are five takeaways related to public health.

1. Immigration fears affect access to health system

About 350,000 of Georgia’s 1 million Latinos are undocumented immigrants, according to the report, but concerns about immigration status and deportation are widespread, said Belisa Urbina, CEO of Ser Familia.

Latinos often live in “mixed status” families or are otherwise fearful of being tracked. That prevents them from applying for government services, said Nikolai Elneser, the community impact officer at nonprofit Neighborhood Nexus.

Close to 15% of Latino children lack health insurance, more than double the 7% of Georgia children across all groups.

At Tuesday’s summit, Gilda Pedraza, executive director of the Latino Community Fund of Georgia, called on the state government to expand Medicaid to include all people, even if they are undocumented.

Not having a driver’s license makes it harder for some to get to and from doctor’s appointments in Atlanta, which has limited public transit.

2. Mental health system lacks Spanish-speaking providers

Intentional self-harm is the seventh leading cause of death among Latinos in Georgia. Latinos are the only group for which self-harm is in the top 10 causes of death, according to the report.

“We see about 1,500 minors a year in services, group and individual therapy, and two-thirds of them present [with] suicidal ideation. … This is very alarming,” Urbina said at the summit.

Some Latinos are reluctant to turn to psychiatric medications for cultural reasons, according to the report, but may trust a provider who takes the time to thoroughly discuss medication.

Parents are especially eager to get services for their children, but have trouble finding Spanish-speaking providers and getting appointments when they are not working, Elneser said.

“We have a tremendous disparity between the people that need the services and the available services that are linguistically relevant,” Urbina said.

Georgia’s certification requirements for foreign health professionals, including mental health workers, are too cumbersome, she said.

She estimates there are 100 fully licensed mental health providers who speak Spanish in the state and maybe only one Spanish-speaking psychiatrist. Her organization will soon hire a Spanish-speaking psychiatric nurse practitioner.

While many Latinos are proficient in English, people want to access services in their own languages, Urbina said. It’s especially important when discussing traumatic or sensitive topics.

Children face particular stresses, including the need to serve as interpreters for their family while dealing with weighty issues. And Latinos in general feel a great deal of anxiety about immigration, leaders said during Tuesday’s summit.

3. Latinas getting inadequate maternal health care

Pregnant Latinas get adequate maternal care at lower rates than the general population in Georgia.

About 22% of the state’s live births are born to Latina mothers who had inadequate prenatal care, higher than the 16% rate for non-Latina mothers.

The inability to get insurance and pay for services is one major barrier, said Roxana Chicas, a professor of nursing at Emory University. They also may have difficulty taking time off work to get care during the day and not be able to get rides to clinics.

“We know that more and more Latinos are moving out into Gwinnett, Cobb and further out, and [there’s] no transportation,” Chicas said.

Women who need to change their diets – because of gestational diabetes, for example – may not get culturally competent guidance about what to eat, Elneser said.

“The healthcare system is lacking cultural competency, and sometimes it’s not a warm environment for some women,” Chicas said.

4. Heat is a public health issue

The report calls on the governments and businesses to expand protections for workers exposed to heat.

Latinos are over-represented in hazardous occupations like construction, hospitality, and farmwork, according to the report, and heat is a particular problem.

Farmworkers are far more likely to die from heatstroke than other types of workers, according to one study cited in the report. The report notes that most H-2A (temporary agricultural visa) workers in Georgia are Latino.

“Many of these workers are workers of color … that don’t have the option of not working outdoors,” said Chicas, who specializes in studying the impact of heat on worker health.

“We have a responsibility to protect these workers while they’re building our homes, while they are harvesting our foods, so that they don’t die on the job from heat stroke, which is preventable,” she said.

It’s hard to know exactly how many people have died due to heat in Georgia because no surveillance system exists, although national numbers can help indicate local trends, Chicas said. It’s hard to identify when heat causes a death. She gave the example of someone who falls due to heat stroke – that death would be counted as death due to a fall and not heat.

Protecting workers from heat is not only the right thing to do, it’s also good business, the report said.

“Safe working conditions (including heat protections) benefit both workers (less injuries and illness) and employers (less absenteeism, lower turnover rates, and disruptions of operations),” the report said.

Six states have enacted worker heat protections, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Pedraza called on U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff to support legislation providing federal heat protections.

5. Trust is key to Latino public health

Leaders emphasized that trusted health workers are key to helping Latino Georgians access health services.

While more Spanish-speaking providers are needed, that’s not the only solution. Urbina would like to see more funding for community health workers.

Her organization has one who works within the Wellstar Health System to help people access and navigate services.

Ser Familia provides group therapy, and there are other evidence-backed, culturally competent programs that social service groups can provide that require a trained, but not necessarily professionally certified, health worker.

“There’s fear of being tracked as a mixed-status family,” Elneser said. “Latino communities have a very strong preference to engage with community organizations,” rather than governmental social services.

The personal touch is key for a community skittish about accessing help, said Dianne Román. As the coordinator of the Latino Community Fund’s Ventanillas de Salud program, she helps Latinos find free, Spanish-language services.

Román makes it clear that the events she organizes are “a safe space” to try to lessen people’s concerns about being deported over their immigration status.

And she serves as a constant point of contact for people in need of help.

“It [is] something more personal, and that’s how I like to work with the community: They know who is providing the services. They can trust you,” Román said.

This story has been updated to correct Roxana Chica’s first name.

Rebecca Grapevine is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Rebecca at rgrapevine@healthbeat.org.